INTRODUCTION

Corticosteroids have been a cornerstone in the management of various respiratory conditions due to their potent anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects. However, their use in respiratory infections, particularly in patients with chronic conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and bronchiectasis, remains controversial1. While corticosteroids can mitigate inflammation and reduce the risk of acute exacerbations, concerns persist regarding side effects, including the potential to aggravate infections. Recent international guidelines have also highlighted that the benefits of corticosteroids depend strongly on timing, severity, and patient selection, particularly in conditions such as sepsis, ARDS, and severe pneumonia2. One of the main controversies surrounding their use in respiratory infections is the balance between benefit and harm in different patient populations. Evidence indicates that corticosteroids may be effective in selected subgroups, such as those with elevated eosinophil counts, but some reports have raised concern that their use in other populations may be associated with adverse outcomes, including increased susceptibility to secondary infections1. Recent studies further confirm that stability of blood eosinophil counts predicts corticosteroid responsiveness in COPD3 and that phenotyping strategies in asthma can optimize treatment outcomes4. Furthermore, debate continues over the role of systemic versus inhaled corticosteroids, with evidence suggesting that inhaled formulations may help reduce systemic adverse effects while maintaining therapeutic benefit5. Another important challenge is the absence of universally accepted guidelines for corticosteroid use in respiratory infections. Although organizations such as the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) provide recommendations, real-world prescribing patterns often diverge due to physician preference, restricted access to biomarker testing, and variability in clinical presentation6. The reliance on clinical judgment rather than objective biomarkers further complicates the standardization of corticosteroid therapy6.

Despite these challenges, corticosteroids continue to be widely used, reflecting the need for further research to clarify their optimal role in respiratory infections. More recent evidence indicates that eosinophilic exacerbations of COPD may represent a distinct clinical entity with implications for corticosteroid responsiveness7, while systematic reviews continue to stress the safety concerns of corticosteroids in severe pneumonia8. This study aims to bridge these gaps by systematically analyzing prescribing patterns, decision-making processes, and perceived efficacy of corticosteroids across a diverse group of physicians. Insights gained from this study could inform evidence-based guidelines and optimize patient outcomes.

METHODS

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Italy between March and June 2024. Participants were recruited through professional medical networks, email invitations, and online forums dedicated to respiratory diseases to ensure a representative sample of clinicians actively involved in the management of respiratory infections. Eligible respondents (n=203) were practicing physicians with at least one year of clinical experience in treating respiratory infections, while residents, medical students, and non-clinical professionals were excluded.

This study was conducted following the principles of good clinical practice and in alignment with the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Given the nature of the study, obtaining formal approval from an ethics committee was not considered necessary. All participants willingly provided written consent before taking part in the survey.

Survey instrument

The survey instrument was developed through an iterative process involving expert review to ensure content validity and reliability. The questionnaire consisted of 11 items covering key topics such as medical specialization and clinical experience, primary reasons for corticosteroid prescription, frequency and rationale for corticosteroid use in acute COPD exacerbations, consideration of inflammatory phenotypes (e.g. eosinophilic vs. neutrophilic) in COPD management, approach to corticosteroid use in bronchiectasis, particularly in cases with Pseudomonas or mycobacterial colonization, determination of corticosteroid dosages and duration of therapy, perceived efficacy of corticosteroids in managing inflammation, strategies for high-risk infections including bacterial colonization, preferences for inhaled versus systemic corticosteroids, and role of biomarker monitoring (e.g. eosinophil count, CRP) in guiding therapy (Supplementary file).

To ensure the reliability of responses, the questionnaire was pilot tested with a small group of respiratory physicians before full deployment. The survey items focused on overall prescribing practices and routes of administration but did not capture details regarding the specific type of corticosteroid (e.g. oral vs intravenous systemic formulations), which represents a limitation of the study.

Statistical analysis

Responses were analyzed using descriptive statistics to summarize categorical variables as frequencies (n) and percentages (%). Comparisons between specialties were performed using chi-squared tests to evaluate differences in response distributions. A two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

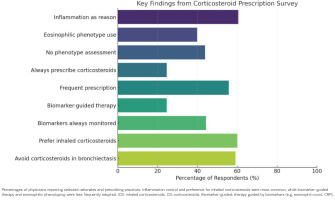

In total, 203 physicians completed the survey, most of whom were pulmonologists (73.9%). Across the 11 survey items, the most frequently reported rationale was reducing airway and lung inflammation (‘inflammation control’), with inhaled formulations generally preferred over oral. Substantial variability was observed between specialties, particularly in the use of phenotyping, biomarker guidance, and prescribing in high-risk infections. Several statistically significant differences across specialties were identified (chi-squared tests, p<0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1

Prescription patterns of corticosteroids in respiratory infections across medical specialties (N=203)

| Item | Response | Total % | Pulmonologists % | GPs % | IM specialists % | ID specialists % | p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General use | Use of corticosteroids | 100 | 73.89 | 13.3 | 7.39 | 5.42 | 0.422 |

| Rationale for use to reduce inflammation | Airway | 60.59 | 69.33 | 48.15 | 60.00 | 45.45 | 0.021 |

| Hyperreactivity | 27.59 | 18.67 | 44.44 | 33.33 | 36.36 | ||

| Other | 11.82 | 12.00 | 7.41 | 6.67 | 18.18 | ||

| Frequency of prescription | Always | 24.63 | 30.67 | 7.41 | 20.00 | 18.18 | 0.003 |

| Frequently | 55.67 | 60.00 | 48.15 | 60.00 | 36.36 | ||

| Occasionally | 19.70 | 9.33 | 44.44 | 20.00 | 45.45 | ||

| Phenotype use | Yes, eosinophilic | 39.90 | 49.33 | 25.93 | 33.33 | 36.36 | 0.019 |

| No | 43.84 | 36.00 | 62.96 | 46.67 | 45.45 | ||

| Other | 16.26 | 14.67 | 11.11 | 20.00 | 18.18 | ||

| Biomarker guidance in COPD | Avoid corticosteroids | 59.11 | 48.00 | 66.67 | 66.67 | 81.82 | 0.001 |

| Yes, biomarker-based | 24.63 | 30.67 | 18.52 | 20.00 | 9.09 | ||

| No, clinical only | 16.26 | 21.33 | 14.81 | 13.33 | 9.09 | ||

| Corticosteroids in bronchiectasis | Avoid corticosteroids | 49.26 | 44.00 | 51.85 | 46.67 | 63.64 | 0.024 |

| Inhaled only | 28.08 | 30.67 | 25.93 | 33.33 | 18.18 | ||

| ICS + OS | 22.66 | 25.33 | 22.22 | 20.00 | 18.18 | ||

| Treatment guidance | Guidelines + response + biomarkers | 51.72 | 56.00 | 37.04 | 53.33 | 63.64 | 0.005 |

| Clinical response only | 34.98 | 29.33 | 48.15 | 40.00 | 18.18 | ||

| Guidelines only | 13.30 | 14.67 | 14.81 | 6.67 | 18.18 | ||

| Perceived efficacy | Very effective | 36.95 | 42.67 | 25.93 | 33.33 | 27.27 | 0.044 |

| Moderately effective | 54.68 | 52.00 | 55.56 | 60.00 | 63.64 | ||

| Poorly effective | 8.37 | 5.33 | 18.52 | 6.67 | 9.09 | ||

| Use in high-risk infections | Only if strictly necessary | 74.38 | 82.67 | 59.26 | 66.67 | 81.82 | 0.026 |

| Never | 25.62 | 17.33 | 40.74 | 33.33 | 18.18 | ||

| Preferred route | Inhaled only | 60.10 | 69.33 | 48.15 | 53.33 | 45.45 | 0.018 |

| Oral only | 7.88 | 4.00 | 14.81 | 6.67 | 18.18 | ||

| Both | 32.02 | 26.67 | 37.04 | 40.00 | 36.36 | ||

| Biomarker monitoring | Always monitor | 44.33 | 53.33 | 25.93 | 33.33 | 54.55 | 0.011 |

| In selected patients | 34.98 | 34.67 | 44.44 | 40.00 | 27.27 | ||

| Never | 20.69 | 12.00 | 29.63 | 26.67 | 18.18 |

Use of corticosteroids

No significant difference was found in corticosteroid prescribing habits based on specialization. Pulmonologists were the largest group of prescribers, but prescribing trends were consistent across all specializations. However, a subgroup analysis revealed that infectious disease specialists were slightly less likely to prescribe corticosteroids compared to pulmonologists and general practitioners.

Regarding the rationale for prescription, the primary reason for prescribing corticosteroids was reducing inflammation (60.6%), followed by treating airway hyperreactivity (27.6%). While pulmonologists were most likely to prescribe corticosteroids for inflammation control, general practitioners were more likely to cite airway hyperreactivity as a key reason.

Most physicians prescribed corticosteroids frequently (55.7%) or always (24.6%). Subgroup analysis showed that pulmonologists were more likely to prescribe corticosteroids frequently or always in acute COPD exacerbations, while general practitioners and internal medicine specialists reported occasional use more frequently.

Consideration of inflammatory phenotypes

Overall, 39.9% of physicians based corticosteroid use on eosinophilic inflammation, while 43.8% did not phenotype inflammation at all before prescribing. Pulmonologists were significantly more likely to use inflammatory phenotyping compared to general practitioners and internal medicine specialists, indicating that access to specialized diagnostic tools may influence decision-making.

With regard to corticosteroid use in COPD, 59.11% of respondents avoided corticosteroids, while 24.6% used biomarkers to guide therapy. Pulmonologists showed a greater tendency to utilize biomarkers compared to other specialists. General practitioners, on the other hand, were more likely to rely solely on clinical symptoms, underscoring the need for broader accessibility to biomarker testing. Regarding bronchiectasis, 49.3% avoided corticosteroids, while 28.1% prescribed inhaled corticosteroids only. Infectious disease specialists were significantly less likely to prescribe corticosteroids in this population, aligning with concerns about worsening mycobacterial infections. Meanwhile, general practitioners displayed the highest variability in prescribing habits.

With regard to the determinants of corticosteroid prescription, the most common approach was a combination of guidelines, patient response, and biomarkers (51.7%). Pulmonologists and infectious disease specialists were more likely to integrate biomarker assessments, while general practitioners and internal medicine specialists placed greater emphasis on patient response. Concerning perceived efficacy, 54.7% found them moderately effective, while 37.0% found them very effective. Pulmonologists were more likely to report corticosteroids as highly effective, whereas general practitioners and internal medicine specialists expressed more skepticism about their efficacy.

Regarding use in high-risk infections, 74.4% avoided corticosteroids unless absolutely necessary. Pulmonologists and infectious disease specialists were significantly more cautious, aligning with concerns about bacterial proliferation. Internal medicine specialists, however, were slightly more open to corticosteroid use in select cases, suggesting a possible role for interdisciplinary consultation in managing these patients. With regard to the preferred route of administration, 60.1% preferred inhaled corticosteroids, while 7.9% preferred oral corticosteroids. Pulmonologists favored inhaled corticosteroids, whereas general practitioners and internal medicine specialists were more likely to use a combination of inhaled and oral forms.

Finally, concerning the monitoring of biomarkers, 44.3% always monitored biomarkers, while 35.0% did so selectively. Pulmonologists and infectious disease specialists were more likely to incorporate biomarker assessments routinely, while general practitioners and internal medicine specialists relied more on clinical judgment. The chi-squared test found a statistically significant difference (Table 1 and Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

This cross-sectional survey sheds light on real-world corticosteroid prescription patterns in respiratory infections across various medical specializations. Although inflammation reduction was consistently reported as the primary rationale for corticosteroid use, our findings revealed considerable variation in prescribing habits – particularly regarding the use of inflammatory phenotyping and biomarker monitoring. These inconsistencies echo the current literature and emphasize the need for more standardized, phenotype-guided approaches1.

Corticosteroids remain central in managing airway inflammation, especially during acute exacerbations of chronic respiratory diseases. However, our data show that only 39.90% of respondents considered eosinophilic inflammation before prescribing, while 43.84% did not assess phenotype at all, despite increasing awareness of the relevance of inflammatory patterns. These findings are in line with previous studies demonstrating increased pneumonia risk in patients with COPD-bronchiectasis overlap treated with inhaled corticosteroids, particularly in the absence of clear phenotyping2.

This deviation from guideline-based practice is noteworthy, especially considering that international recommendations – such as those from the GOLD initiative – promote biomarker-guided and phenotype-specific corticosteroid use3. Yet, the real-world data we present here suggest that such practices are not consistently applied, particularly outside of pulmonology.

Importantly, our results indicate that pulmonologists are more likely to integrate biomarkers and phenotypes into their decision-making, while general practitioners and internal medicine physicians rely more heavily on clinical judgment. Specialty-related differences may explain some of these patterns. Infectious disease specialists showed a lower tendency to prescribe corticosteroids, likely reflecting a more cautious approach toward infection risk management. General practitioners, by contrast, emphasized airway hyperreactivity more often, consistent with the broader range of respiratory conditions, including asthma, encountered in primary care. Their more frequent occasional use of corticosteroids, together with that of internal medicine physicians, may reflect differences in access to phenotypic assessments and variable adherence to COPD guidelines. In addition, the higher variability in bronchiectasis prescribing observed among general practitioners could be linked to more limited familiarity with this condition, which is typically concentrated in specialist settings. Further differences were also evident: many physicians reported relying on a combination of guidelines, patient response, and biomarkers, underscoring the need for greater standardization; pulmonologists more frequently rated corticosteroids as highly effective, possibly reflecting the more severe inflammatory cases under their care; internal medicine specialists appeared more open to cautious use in high-risk infections, suggesting a potential role for interdisciplinary consultation; and variability in preferences across specialties likely mirrors broader differences in management strategies. Finally, the more frequent biomarker monitoring among pulmonologists and infectious disease specialists indicates that specialty continues to shape the extent to which objective measures are incorporated into clinical decision-making. This gap in practice may reflect disparities in access to diagnostics, training, and familiarity with current evidence. The risks of systemic corticosteroid overuse – including immunosuppression, metabolic disturbances, and infection – are well documented, and our data highlight how reliance on empirical judgment without biomarker confirmation may contribute to overtreatment9,10.

In support of a more refined approach, several meta-analyses and trials have shown that corticosteroid benefits are concentrated in select subgroups, especially those with eosinophilic inflammation or systemic hyperinflammation11,12. However, only 24.63% of our respondents reported routinely using biomarkers to guide therapy, underscoring the underutilization of readily available tools.

The role of corticosteroids in bronchiectasis, particularly in patients colonized with Pseudomonas or non-tuberculous mycobacteria, remains controversial. Our data show that most physicians avoid corticosteroids in such cases, especially infectious disease specialists, consistent with concerns about worsening chronic infection and bacterial proliferation2.

Beyond chronic disease, corticosteroids have been investigated in severe infections such as septic shock and community-acquired pneumonia13, where they appear to reduce treatment failure in highly inflamed patients14. Our survey confirms a more cautious approach among infectious disease specialists, which likely reflects greater awareness of these indications and their limitations.

The recent COVID-19 pandemic further highlighted the importance of context and timing in corticosteroid use. Our findings align with clinical experiences showing that short-course corticosteroids can improve outcomes in selected hospitalized patients – particularly when applied early in the disease course15.

Notably, the importance of corticosteroid stewardship is increasingly recognized in other medical fields, such as rheumatology. Guidelines in these specialties stress the need to balance efficacy with long-term safety and advocate for minimizing unnecessary exposure. This paradigm may be highly relevant in respiratory care, especially as we move toward more personalized medicine16.

However, even in the COVID-19 setting, evidence has shown that the benefits of corticosteroids are not universal, and inappropriate timing or patient selection may be harmful10. These findings underscore the broader need for clinicians to adopt evidence-based, biomarker-driven strategies in daily practice.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the results may have limited generalizability, as the survey was conducted exclusively among physicians practicing in Italy, with a predominance of pulmonologists among respondents. Second, the reliance on self-reported survey data introduces the possibility of misclassification bias. Third, the survey did not explicitly differentiate whether responses referred to the management of inpatients, outpatients, or both, which may limit the interpretation of some findings. Furthermore, the survey did not investigate the type of corticosteroid prescribed in detail, beyond distinguishing inhaled from systemic routes, and this omission may limit the interpretation of prescribing patterns across different formulations. Finally, respiratory infections were not addressed separately by disease. In particular, conditions such as community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) were not individually assessed, despite recent evidence17 showing that hydrocortisone reduced 28-day mortality in patients with severe CAP admitted to the ICU. This lack of disease-specific focus limits the granularity of our findings and highlights the need for future studies to investigate prescribing patterns in defined infections such as CAP across different care settings. These factors should be considered when extrapolating our results, and future studies including more diverse international samples and clearly defined patient care settings are warranted.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study confirms both consistencies and variations in corticosteroid prescribing across specializations. While inflammation control remains a common goal, the limited adoption of phenotyping and biomarker monitoring, especially among non-pulmonologists, signals a gap between guidelines and practice. Targeted educational interventions, better diagnostic access, and clearer guidance could support safer, more effective use of corticosteroids in respiratory infections.