INTRODUCTION

Sarcoidosis is an inflammatory disease of unknown etiology, characterized by noncaseating granulomata affecting multiple organs1. Although the exact pathophysiology remains incompletely understood, increasing evidence suggests that granulomata formation involves a complex interplay between genetic susceptibility and environmental stimuli. Sarcoidosis affects multiple organ systems, and frequently presents with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, pulmonary infiltrates as well as joint, ocular and cutaneous lesions2. Clinical course of the disease is heterogenous, ranging from totally asymptomatic to life-threatening disease3.

Due to the considerable heterogeneity of sarcoidosis manifestations, no universally accepted treatment guidelines have been established by major international societies such as the ERS or ATS. However, in 2021, the European Respiratory Society (ERS) published Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Treatment of Sarcoidosis, which represents an important step forward but still requires further validation and broader implementation. The prevalence of the disease varies significantly across different parts of the world, from 1–5 per 100000 in Asia4, to 60 per 100000 in the USA and 140–160 per 100000 in Sweden5.

In this report, we exhibit an interesting case of a patient who presented with mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy along with hypercalcemia and chronic kidney disease.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 65-year-old female of German origin, current smoker, without occupational exposure to inhaled substances, was referred to our institution with fatigue, thoracic pain in the interscapular area and joint pain for the past 3 months. Her past medical history included diabetes mellitus type II with symptoms of diabetic neuralgia and dyslipidemia, for which she was treated with insulin glargine, sitagliptin, gabapentin and tramadol/acetaminophen. During the past three months the patient underwent a series of medical examinations, one of which was chest CT as part of the investigation for her fatigue and chest pain. High resolution chest computed tomography (HRCT) revealed mediastinal lymphadenopathy in stations 2, 3, 4, 5, 7 and 10 (Figure 1), along with bilateral patchy infiltrates in the pulmonary parenchyma (Figure 2).

Figure 1

A) and B): Patient’s chest CT showing the enlarged upper paratracheal lymph nodes (LN 2L) and right lower paratracheal (LN 4R)

Vital signs were as follows: blood pressure 130/64 mmHg, heart rate 64 bpm, oxygen saturation 96% on room air, and body temperature 36.3°C. Lung auscultation revealed end-inspiratory crackles, primarily in the lower lung fields. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

An electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus rhythm at 59 bpm, a PR interval at the upper limit of normal (200 ms), and a normal corrected QT interval (QTc: 372 ms), with no other abnormalities.

Initial laboratory tests demonstrated hypercalcemia (serum calcium: 14.5 mg/dL, normal range: 8.5–10.5 mg/dL), impaired renal function (creatinine clearance: 32 mL/min), elevated C-reactive protein (CRP: 3.85 mg/dL, normal range: <0.1 mg/dL). Urinalysis revealed a total protein concentration of 27 mg/dL, hematuria, pyuria, and abundant microbial presence. A 24-h urine collection showed elevated urinary calcium (478.4 mg/24 h, normal range: 100–300 mg/24 h) and total protein (0.8 g/24 h normal range: <0.25g) whereas creatinine was within normal limits (1.07 g/24 h, normal range: 0.8–1.8 g/24 h). In view of the renal insufficiency and hypercalciuria, renal ultrasonography and urethrography were performed, which identified a kidney stone causing obstruction and dilation of the right urinary tract.

Investigations

The two urgent clinical concerns requiring further investigation were hypercalcemia and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. A systematic diagnostic approach was undertaken, with initial emphasis on identifying the underlying cause of hypercalcemia.

Primary hyperparathyroidism was excluded by the finding of normal serum parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels. Given that malignancy – particularly hematological neoplasms and solid tumors – is a common etiology of hypercalcemia, further workup included serum and urine protein electrophoresis, immunofixation, serum free light chains (kappa and lambda), and immunoglobulin levels. All results were within normal limits, and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen showed no additional pathological findings.

Following the exclusion of parathyroid-related and malignant causes, less common etiologies such as vitamin D toxicity and other endocrinopathies were also considered and subsequently excluded. Granulomatous diseases can also cause hypercalcemia and were considered during differential diagnosis.

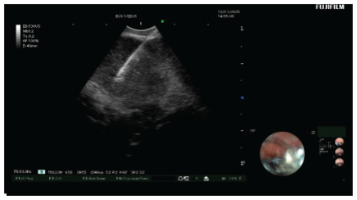

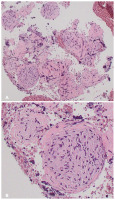

EBUS-TBNA was used to sample lymph node stations 4R, 7R, and 11R (Figure 3), and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed in the right middle lobe. Histopathological analysis showed non-caseating granulomas with epithelioid histiocytes and surrounding lymphocytes (Figure 4), consistent with non-necrotic granulomatous inflammation. Rigorous laboratory and cytological examination of BAL suggested no other potential diagnosis.

Figure 4

Histopathology image of non-caseating granulomatous inflammation in the mediastinal lymph node: A) Four granulomas are seen with no necrosis in the center; B) Enlarged epithelial cells are in the center of the granuloma, surrounded by lymphocytes

For the evaluation of the lung impairment due to sarcoidosis, lung function tests were performed. Spirometry tests showed reduction in FVC (75% of the predicted), and diffusion testing revealed TLCO at 75% of the predicted. These results were interpreted as a mild lung impairment due to sarcoidosis.

Differential diagnosis

Diagnosis of sarcoidosis generally requires fulfillment of three criteria, based on the American Thoracic Society expert consensus: 1) clinical features considered suggestive of the disease, 2) histologic evidence of non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation in at least one or more tissue samples, and 3) exclusion of alternative causes of granulomatous disease1.

Clinical and laboratory findings in our patient indicative of sarcoidosis included hypercalciuria, hypercalcemia, chest pain, and fatigue. To exclude other granulomatous diseases, infectious, environmental, and drug-related causes were considered. Infectious etiologies like fungal infections or non-tuberculous mycobacteria were unlikely due to the absence of epidemiological risk and negative results in fungal stains, cultures, Ziehl-Neelsen stains, and tissue cultures. Foreign body inhalation, which typically presents as central material within granulomas surrounded by epithelial cells, was also excluded, since no such finding was observed in the histological specimens. Occupational exposure was ruled out based on the patient’s history.

A detailed drug history was also obtained to exclude drug-induced sarcoidosis, especially by immune checkpoint inhibitors, antiretroviral drugs, interferons or TNF-α antagonists2,3. Considering the above findings, our patient fulfilled all three ATS diagnostic criteria, making sarcoidosis the most likely diagnosis.

Treatment strategy

Upon the diagnosis of sarcoidosis with renal impairment, treatment with immunosuppressive drugs was promptly initiated. According to BTS guidelines, the initial pharmacological treatment for sarcoidosis with target organ disease is 20–40 mg of prednisone qd. In this case, 80 mg methylprednisolone were administered intravenous daily due to the significant renal impairment and the increased BMI of the patient. Such immunosuppressant dose resulted in the reduction of symptoms, with less joint pain and fatigue, and calcium levels (decline by 1.4 mg/dL in 5 days), suggesting a good response to therapy. For the treatment of the urinary obstruction a pigtail catheter was endoscopically placed on the right ureter.

To screen for other sarcoidosis manifestations, the patient had an eye/retinal examination which revealed no abnormalities, and a cardiac PET scan was also planned. At discharge, the patient was advised to continue methylprednisolone with progressive tapering, undergo laboratory tests including 24-h urine calcium, and repeat a chest CT scan on follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Our patient presented a clinically notable case featuring hypercalcemia, nephrolithiasis, and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, all of which were finally attributed to sarcoidosis following extensive evaluation. Sarcoidosis with nephrocalcinosis is not very common; a study conducted in Greece reported renal impairment in 17.7% of patients, often associated with a more advanced disease phenotype and worse outcomes6.

Another important consideration is the timing of treatment initiation in sarcoidosis, as therapy is not always required. Clinical decision-making necessitates a detailed assessment to determine disease extent and subsequent target organ involvement and to stratify morbidity and mortality risk for each individual, as emphasized in the ERS clinical practice guidelines4. In our case, treatment was started promptly due to renal disfunction, as the kidneys represent a target organ.

This case report is of clinical significance due to the extensive diagnostic evaluation required and the multiple signs and symptoms that needed detailed examination. Although the patient’s clinical image was improved when corticosteroids were administered and the urinary obstruction was surgically removed, the long-term follow-up is to be determined, to further support this treatment plan.

Renal impairment in sarcoidosis is usually oligo-asymptomatic and often underdiagnosed in patients that lack pulmonary involvement. Nephrocalcinosis, with or without stone formation, and interstitial nephritis are the two more common manifestations of renal disease and can lead to end stage renal failure. Therefore, clinical vigilance for renal impairment due to sarcoidosis is advocated in relevant guidelines7.

CONCLUSION

Although sarcoidosis’s prevalence is up to 0.14–0.16% in some northern European countries8 and is the most common interstitial lung disease in Greece6, formal guidelines need refinement. As a result, managing each patient with potential sarcoidosis depends on the ERS or ATS practical clinical guidelines and the expert’s opinion. In this case report, the need for proper diagnostic algorithm and treatment due to mild lung disfunction and nephrocalcinosis is emphasized.