INTRODUCTION

Bronchial asthma is a clinically heterogeneous disease among children and adults characterized by chronic inflammation and narrowing of small airways. Asthma can present with several symptoms, including wheezing, shortness of breath, persistent cough, chest tightness, and airflow limitation that vary in intensity and over time1. In 2019, about 262 million people were affected by asthma, and 455 thousand deaths occurred, with the vast majority being reported in countries in low- and low-middle-income, where access to medical care is limited2. Interestingly, patients with severe asthma are reported to contribute disproportionately higher costs to the total asthma-related direct expenditures3.

A subtype of difficult-to-treat asthma known as severe asthma is characterized by poor symptom control and frequent exacerbations, despite adherence to maximal optimized treatment and management of triggering factors, or asthma that worsens when high-dose treatment is decreased4. It is estimated to account for 3.5–5.4% of asthmatic adults and 0.3–1% of asthmatic children5. Mucus dysfunction has been well documented in patients with severe and fatal asthma6-8 and has recently also been described in individuals with mild asthma9. Furthermore, mucus plugging has emerged as a novel treatable trait, suggesting that targeted therapy with biologic agents could be beneficial10.

In this narrative review, we provide an overview of the basic pathology of mucus plugs, examining the clinical impact of mucus plugging on asthma symptomatology and severity, with the aim of investigating potential implications for the selection of biological treatments in patients with poorly controlled asthma.

Within the context of this narrative review we conducted on 8 December 2024 a PubMed search using the queries: [‘mucus’ AND ‘asthma’], [‘mucus’ AND ‘asthma’ AND ‘smoking’], [‘mucus’ AND ‘asthma’ AND (‘biological therapy’ OR ‘biological agents’ OR ‘biological treatment’ OR ‘immunotherapy’ OR ‘monoclonal antibodies’)], [‘mucus’ AND ‘asthma’ AND (‘omalizumab’ OR ‘mepolizumab’ OR ‘benralizumab’ OR ‘tezepelumab’ OR ‘omalizumab’ OR ‘dupilumab’)]. We included only articles published in English with no start date. We selected articles that primarily focused on the main areas of our narrative review, including: 1) the immunopathology of mucus plugging; 2) the assessment of mucus in clinical practice, regardless of smoking habit; and 3) the potential response to biologics in patients with poorly controlled asthma. Editorials and conference papers were not excluded in this review.

Our narrative search identified 4156 unique results. After removing duplicate entries, two independent reviewers evaluated the titles and abstracts. Subsequently, 53 items (22 observational studies, 7 review articles, 6 case-reports, 4 post-mortem studies, 3 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 3 laboratory trials, 2 editorials, 1 non-randomized interventional trial, 1 study protocol of an RCT, 1 post hoc analysis of an RCT, 1 letter to the editor, 1 meeting abstract, 1 chapter book) were identified.

Following inclusion, articles were categorized into four categories as follows: 1) mucus plug pathology; 2) eosinophil-mucus interaction; 3) mucus plug phenotype; and 4) smoking effect; and 5) biologic therapies.

MUCUS PLUGGING AND BIOLOGIC THERAPIES FOR ASTHMA

Mucus plug pathology

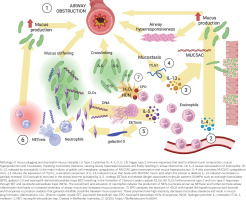

Mucociliary clearance is the first defense mechanism of airway epithelium against environmental inhaled pathogens and noxious gases. Epithelial cells produce a gel-like layer of mucus to trap these pathogens11. The mucus-entrapped particles and dissolved gases are carted away by the coordinated moves of cilia. Airway mucus is primarily composed of water and a small percentage of solids, including about 1% of proteins12. The dominant proteins in mucus are mucins, specifically MUC5AC and MUC5B, while MUC2 is present in negligible amounts13. Research demonstrates that the production of MUC5AC and MUC5B occurs in distinct locations: MUC5AC is found in goblet cells and in the terminal secretory ducts of submucosal glands, while MUC5B is primarily located in the mucous cells of submucosal glands and, to a lower degree, in secretory cells of the airway epithelium in the trachea and bronchi14.

In many muco-obstructive airway diseases including bronchial asthma, airway gel often appears abnormally viscous. Notably, autopsies have demonstrated how crucial mucus plugging is in fatal asthma6,7,15. Obstruction in the airway lumen was also confirmed in a large post-mortem study, where plugging consisted of a mixed content of mucus and inflammatory cells that varied remarkably between patients8. The formation of pathologic airway mucus in asthma may involve extracellular MUC5AC- tethering to epithelial mucus cells that affect mucociliary clearance14. Very recently, an arising role of a secreted component of interleukin-13 (IL-13) -induced mucus, intelectin-1 (ITLN-1), has been proposed. More specifically, it has been found that ITLN-1 protein binds the MUC5AC and when this protein is deleted in airway epithelial cells, IL-13-induced mucostasis is partially reversed. The authors also provided evidence of a genetic variance in ITLN-1 that suppresses gene and protein expression, indicating a protective role to the airways from the development of mucus plugs16.

A relative change in the MUC5AC:MUC5B ratio has been observed in multiple studies with different methodologies and the more frequent finding is the predominance of MUC5AC over MUC5B9,17,18. Interestingly, changes in MUC5AC and MUC5B gene expression have been also repeatedly described in all asthma stages19-21. Notably, MUC5AC upregulation tends to be more persistent and is usually accompanied by goblet cell hyperplasia.

Eosinophil-mucus interaction

The association between eosinophils and mucus plugs was thoroughly examined by Dunican et al.22, who reported a linear correlation between sputum eosinophils, the amount of mucus plugs and airway obstruction. Tang et al.23 also showed a positive correlation between mucus plugs and sputum eosinophils. Indeed, eosinophils can lead to increased and abnormal mucus production by activating cytolysis, which releases danger-associated molecular patterns, including galactin-10, high mobility group box, eosinophil peroxidase and eosinophil-derived extracellular traps (EET)12. When eosinophils undergo EETosis – a pathway of eosinophilic death – galactin-10 is released24, resulting to formation of Charcot-Leyden Crystals (CLCs)25. CLCs trigger T helper 2 (Th2) and non-Th2 responses and further promote inflammation, induced by EET and neutrophil extracellular traps and mucus production12. Therefore, mucus plugs may be the result of a vicious circle between eosinophils, CLCs and danger signals that lead to more airway inflammation12, but the involvement of CLCs in chronic mucus plugging and the underlying mechanism of persistent plugs in the same segments of the lung has not been yet adequately studied26.

Conversely, altered mucin composition has also been reported to contribute to airway eosinophilic inflammation, indicating a two-way relationship12. Interestingly, an increased MUC5AC:MUC5B ratio was correlated with sputum eosinophilia among asthma patients17. A possible mechanism is reduced eosinophilic apoptosis since Singlec-F (a pro-apoptotic surface protein specifically expressed on mouse eosinophils) is described to interact with glycoepitopes in the MUC5B and induce their death in animal studies27. A direct role of IL-13 in mucin gene expression and upregulation is also well described 14,28. The pathophysiological mechanisms leading to mucus plugging and the contribution of eosinophils to altered airway mucus are briefly illustrated in Figure 1.

Mucus plug phenotype: a new phenotype for clinical practice?

Mucus hypersecretion appears to play a significant role in severe and even mild asthma patients causing airflow obstruction, uncontrolled airway inflammation and more frequent exacerbations10,22,23,29. Indeed, persistent mucus plugging in asthma is currently arising as a novel phenotype (mucus plug phenotype)10,22,23,29. In greater detail, Dunican et al.22 examined the association between mucus plugs and airflow obstruction in severe asthmatic patients by developing a scoring system in asthma patients from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) in order to quantify mucus plugs on multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) lung scans. Airway mucus score was negatively associated with prebronchodilator spirometric values of forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC) and FEV1/FVC ratio of predicted volume, indicating a strong association between mucus plugs and lung function. Moreover, patients with high mucus scores were more frequently categorized as severe asthmatics as they needed higher doses of medication or had lower asthma control test (ACT) scores, even though chronic mucus hypersecretion symptoms were not sensitive or specific to determine the mucus plug phenotype. Interestingly, the authors showed that mucus plugs do not coexist with bronchiectasis22. Subsequently, Tang et al.23 compared mucus plug scores from MDCT lung scans of SARP-3 patients over a 3-year period and suggested that mucus plugs can exist for minimum three years in the same bronchopulmonary segment and can also be associated with changes in FEV1% and loss of lung function. The researchers also found significantly more frequent exacerbations in asthma patients with persistent mucus plugs (p<0.001), supporting the importance of mucus plug phenotype. A year later, Chan et al.10 tried to determine whether mucus plugging can be associated with various phenotypic characteristics in patients with moderate to severe asthma in a real-life single-center retrospective study. Patients with mucus plugs had more frequent severe exacerbations, worse spirometric values and higher levels of routinely measured Th2 inflammation biomarkers, such as blood eosinophil count, total IgE and fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO). This study supports the conclusions from the two previous SARP-3 studies and highlights the importance of considering mucus plug phenotype in severe asthma when deciding about biologic therapies.

Smoking

It is currently well described that individuals with asthma who smoke usually have worse clinical outcomes and quality of life30 and potentially a neutrophilic inflammatory response31, although the underlying cellular profile remains controversial32,33. Oguma et al.34 conducted a prospective observational multi-center study to assess whether smoking status and underlying airway inflammation affect the relationship between mucus plugs, asthma exacerbations and airflow limitation. Researchers compared the association of CT mucus plug score with exacerbation frequency and FEV1 between non-eosinophilic and eosinophilic asthma patients (as defined by sputum eosinophil percentage equal or maximum to 3%), according to smoking status34. Mucus plug score and annual exacerbations were significantly associated in the eosinophilic group, irrespective of smoking status (p<0.01). Additionally, a statistically significant correlation was noted between mucus plug score and FEV1% in the non-smoker, either eosinophilic (p<0.001) or non-eosinophilic group (p=0.03), while this relationship was found statistically significant only in the smoker eosinophilic group (p=0.03)34. Audousset et al.26 also tried to clarify these relationships in individuals with moderate to severe asthma, including both smokers and ex-smokers. Their study revealed that even though mucus plugs were present regardless of smoking status, there was a strong correlation between mucus plug score and the type of airway inflammation that differed depending on smoking status. In the non-smoking group, sputum eosinophilic count was correlated with airway mucus plugging26, a relationship supported by previous studies22,35,36, whereas in the group of active and former smokers, mucus score was associated with sputum neutrophilic count26.

Biologic therapies

The description of the novel mucus plug phenotype raises an important question: ‘Can biologic agents help us unplug the airways?’. To date, there is limited evidence regarding the effect of therapeutic agents on mucus plug scores and whether the decrease of mucus plugging is related to clinically significant outcomes for patients. One of the most novel approved therapeutic agents for asthma is tezepelumab, a human monoclonal antibody that blocks the activity of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), an epithelial cell-derived cytokine involved in asthma pathophysiology, both Th2 and non-Th2 mediated. Recently, a post hoc analysis of the CASCADE study37,38 revealed a decrease of mucus plugs score compared with the placebo, which collated with improvements in lung function39. A key strength of this analysis is the randomized double-blind design of the CASCADE study. However, there was a slight imbalance in the distribution of mucus plugs at baseline between the subgroups and less evaluable CT scans were available in the tezepelumab group. It is also noted that the binary scoring system, which scores only the presence or absence of mucus plugs, does not evaluate other characteristics, such as the number or size of mucus plugs39,40. According to Cedano et al.29, an important limitation of this study is the absence of long-term follow-up, which could provide a clearer understanding of the role of mucus plugs and whether biologic agents may affect them, as previously suggested by Tang et al.23.

Benralizumab is an anti-interleukin-5 receptor alpha-chain antibody (IL-5Rα)41 reported to reduce both peripheral blood and airway eosinophils42, so several studies hypothesized that the reduction of eosinophils would reduce mucus hypersecretion43-46. Takimoto et al.45 first reported a case of a 75-year-old non-smoking female patient with an asthma attack who was treated with benralizumab. Although peripheral eosinophils were almost depleted, the patient developed new atelectasis by mucoid impaction four months after the administration of benralizumab. The researchers hypothesized that the development of mucus plugs on therapy may involve residual lung eosinophils or eosinophil-independent pathways of inflammation, but sputum samples before and after treatment were not available for further analysis. Subsequently, McIntosh et al.46 performed a clinical study on 29 patients with poorly controlled asthma, measuring the 129Xe MRI ventilation change after a unique dose of benralizumab and the relationship of this change with airway mucus. Pulmonary 129Xe MRI ventilation defect percentage (VDP) measures sensitively the asthma airway dysfunction caused by airway hyperresponsiveness, remodeling and luminal mucus occlusions, and can be highly predictive of asthma control. On day 28 after the administration, 129Xe MRI ventilation and Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ)-6 score were significantly improved in participants with five or more mucus plugs (p=0.006). Researchers also generated a multivariate model revealing that VDP and CT scan mucus score before treatment were significant predictors of ACQ-6 score change, as measured 28 days after benralizumab administration46 (p<0.001). However, the main limitation of this study was the small cohort size and the presence of fewer participants in the subgroup with five or fewer mucus plugs46. Therefore, McIntosh et al.47 continued to evaluate these patients at 1 year and subsequently at 2.5 years after the benralizumab initiation to determine whether the early response and mucus resolution observed at 28 days persisted in those who remained on long-term therapy. Of the 29 participants of the original study, sixteen returned for a follow-up at one year and thirteen participants at two and a half years while on treatment with benralizumab. In this longitudinal evaluation, researchers observed significant improvement in mean CT mucus plug score at two and a half years compared to baseline (p=0.03), before benralizumab administration, while in 6 out of 8 participants with previous occlusions, plugs decreased significantly or even disappeared. Persistent MRI ventilation defect improvements were also observed after two and a half years of ongoing benralizumab treatment. Another finding was that MRI VDP and CT mucus score measured before treatment independently predicted the ACQ-6 response after two and a half years of continuous therapy47. Furthermore, Hearn et al.43 aimed to clarify if different mucus plug score at baseline CT is associated with differential response to benralizumab. In a cohort of 116 severe asthma patients, there were no significant differences in mean FEV1, annualized exacerbation rate, reduction of oral corticosteroids and improvement in asthma control tests between the group with and without mucus plugs, respectively43. Thus, the authors suggested that the clinical effectiveness of benralizumab is not affected by mucus plugging43. On the other hand, an observational study44 analyzing CT mucus plugs before and approximately four months after benralizumab initiation, showed that the amount of mucus plugs decreased significantly after immunotherapy (p<0.001). This study also revealed that the amount of mucus plugs correlated positively with sputum eosinophil count and eosinophil cationic protein in the sputum supernatants and negatively with FEV1 and ACT score44.

Omalizumab, an anti-IgE recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody, is the world’s first biologic agent approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of asthma. In a previous study, Shi et al.48 compared pre-treatment and post-treatment chest CT scans of patients with poorly controlled asthma. The authors concluded that there was a significant reduction in the number of mucus plugs after four months of omalizumab treatment (p<0.05)48.

Case reports have also provided evidence that dupilumab may be effective in resolving mucus plugs. Dupilumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that targets the interleukin-4 receptor alpha subunit (IL-4Rα), suppressing both IL-4 and IL-13 and, therefore, Th2-mediated inflammation41. Svenningsen et al.49 first reported a case of a woman aged 39 years with severe asthma who was initially treated with other biologics (omalizumab, mepolizumab, reslizumab), but airway mucus in the CT scan decreased only after a 5-month treatment with dupilumab. Post-dupilumab MRI ventilation also improved to the point where no residual ventilation defects were observed49. Tashiro et al.50 recently reported another case of a female aged 79 years with a recent asthma diagnosis who was initially treated with mepolizumab with no improvement in CT mucus plug score, FeNO or lung function. The patient was then switched to dupilumab and after 3 months of treatment mucus plugs resolved50. In addition, Anai et al.51 reported a case of severe eosinophilic asthma with frequent exacerbations and multiple mucus plugs with bronchiectasis. After 16 weeks, most mucus plugs disappeared in the CT scan and asthma control improved with no exacerbations observed during the follow-up period51. Furthermore, another case demonstrated that a single dose of dupilumab was effective in a patient with severe asthma, as the mucus plugs did not reappear for over a year after administration52. Lastly, Svenningsen et al.53 performed a single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial where dupilumab not only affected the larger airways by improving ventilation as quantified by 129XeMRI use, but also improved small airway function. Improvement of the latter was indicated by the reduction of CT biomarkers of airway mucus such as mucus score, wall area percentage, lumen area and gas trapping as well as oscillometry measures53.

Concerning mepolizumab, an anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibody, there is only one reported case of a patient aged 85 years with severe asthma where CT scan mucus plugs disappeared after 6 months of treatment54. Interestingly, there are no published studies assessing the association of reslizumab with mucus plugs, to the best of our knowledge. Currently approved biologic agents and studies evaluating their effect on mucus plugging are presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1

Biologic agents with corresponding studies regarding mucus plugging in bronchial asthma patients

| Study Year | Design | Patients | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benrlizumab | |||

| Takimoto et al.45 2020 | Case report | 75-year-old female patient with an asthma attack, previously uncontrolled asthma | New atelectasis by mucoid impaction 4 months after the administration of benrlizumab; depletion of BEC. |

| McIntosh et al.46 2022 | Open label single-arm study | 29 patients (27 with baseline CT imaging) with poorly controlled asthma; 28 days follow-up after single benrlizumab dose | Overall improvement in BEC, VDP, ACQ-6, AQLQ and peripheral airway resistance; Significant improvement in VDP and ACQ-6 was found only in the subgroup with ≥5 plugs (p=0.006); VDP and CT mucus score before therapy were significant variables for ACQ-6 improvement after benrlizumab injection (p<0.001). |

| Hearn et al.43 2022 | Retrospective real-life study | 116 patients with severe eosinophilic asthma; 1 year follow-up | The presence of mucus plugs at baseline CT was not associated with differential response to benrlizumab. |

| McIntosh et al.47 2023 | Longitudinal open label single-arm study | 12 patients with poorly controlled eosinophilic asthma; 2.5 years follow-up | CT mucus score significantly improved (p=0.03); Baseline VDP and mucus score independently predicted ACQ-6 score after 2.5 years treatment. |

| Sakai et al.44 2023 | Single-arm observational study | 12 patients with severe uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma; 4 months follow-up | Significant reduction in CT mucus plugs counts after benrlizumab treatment (p<0.001); Number of mucus plugs correlated with sputum eosinophil percentage and sputum ECP and inversely correlated with FEV1. |

| Dupilumab | |||

| Svennigsen et al.49 2019 | Case report | 39-year-old female with severe asthma; 5 months follow-up | CT mucus score reduction from 8 to 1; Complete normalization of inhaled hyperpolarized 3He MRI ventilation heterogeneity after treatment. |

| Anai et al.51 2022 | Case report | 29-year-old male with severe eosinophilic asthma; 16 weeks follow-up | CT mucus score from 9 to 3; no exacerbations during the observation period; Decrease in FeNO; Improvement in ACT and FEV1. |

| Svenningsen et al.53 2023 | Single-center randomized double-blind placebo controlled trial | 25 adults (13 dupilumab, 11 placebo) with uncontrolled moderate to severe asthma and T2 inflammation; 16 weeks follow-up | Greater improvement in CT mucus score, WA%, CT gas trapping and VDP in the dupilumab than in the placebo group; In dupilumab group, baseline mucus score was correlated with the change in VDP, oscillometry measures and FEV1; The change in VDP was also correlated with the change in gas trapping. |

| Hasegawa et al.52 2024 | Case report | 62-year-old male with poorly controlled asthma | Disappearance of mucoid impactions after single dose dupilumab and no recurrence in CT scan after 1.5 years. |

| Tashiro et al.50 2024 | Case report | 79-year-old female asthma patient with high FeNO and BEC; switch from mepolizumab to dupilumab | CT mucus plugs were augmented with initial mepolizumab treatment but completely disappeared after 3 months of dupilumab treatment. |

| Mepolizumab | |||

| Hamakawa and Ishida54 2024 | Case report | 85-year-old male with severe asthma | Disappearance of CT mucus plugs 6 months after mepolizumab administration. |

| Omalizumab | |||

| Shi et al.48 2024 | Single-center prospective observational study | 61 patients with poorly controlled refractory asthma; 4 months follow-up | CT mucus score decreased from 1 to 0 after treatment; Significant decrease in the WA% and in the ratio of wall thickness and outer radius (p<0.05) (results available only for 25 patients). |

| Tezepelumab | |||

| Nordenmark et al.39 2023 | Analysis of the CASCADE trial* | 82 patients (37 tezepelumab, 45 placebo) with uncontrolled, moderate-to-severe asthma; 28 weeks follow-up | Greater absolute change from baseline CT mucus score in patients receiving tezepelumab than placebo; Higher baseline mucus score correlated with reduced baseline lung function and higher baseline BEC; Ιn tezepelumab group, reduction in mucus score correlated with improvement in lung function and reduction in BEC and EDN. |

* CASCADE: study to evaluate tezepelumab on airway inflammation in adults with uncontrolled asthma (NCT03688074).

ACQ-6: Asthma Control Questionnaire-6 score. AQLQ: Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire. ACT: asthma control test. BEC: blood eosinophil count. ECP: eosinophil cationic protein. EDN: eosinophil-derived neurotoxin. FeNO: fractional exhaled nitric oxide. FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1s. VDP: ventilation defect percentage. WA%: CT wall area percentage.

Table 2

Effectiveness of biologic agents in CT mucus plug score reduction in poorly controlled asthma patients

| Benralizumab | Tezepelumab | Dupilumab | Omalizumab | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Year | Mc Intosh et al.47 2023 | Nordenmark et al.39 2023 | Svenningsen et al.53 2023 | Shi et al.48 2024 |

| Design | Longitudinal open label | RCT | RCT | Prospective observational study |

| Number of patients receiving mAb | 12 | 37 | 13 | 25 |

| Observation period | 2.5 years | 28 weeks | 16 weeks | 4 months |

| Change in the MDCT mucus plug score | -2.0 ± 5.0* | -1.7 ± 2.6* | -4 (95% CI: -7 – -1) | -1 (p<0.05) |

Implications

In this narrative review, we offered a basic overview of mucus plugging pathology and its association with asthma phenotype and severity. As mucus plugging is considered a novel trait in the field of severe asthma10, there is ongoing research focusing on potential therapeutic targets. Biologic therapy is currently the most novel and promising treatment for patients with poorly controlled asthma, thus potential implications regarding specific agent selection for mucus unplugging were also investigated in this review. Nevertheless, quality and amount of published data are currently limited for this question to be answered.

To date, and to our knowledge, no published clinical trials exist where biologic agents are head-to-head compared in terms of treatment efficacy, regarding mucus plugging in severe asthma. The only comparison between biologic agents was conducted in a recent small comparative retrospective study of Venegas et al.55. In the latter, residual mucus plugging was significantly higher in patients treated with anti-IL5 monoclonal antibodies compared with subjects on dupilumab (p=0.005). However, apart from this conference paper55, the rest of the relevant published studies are characterized by differences in study protocols, cohort sizes, and observation periods, making it rather difficult to come to a definite conclusion regarding the efficacy of one biologic agent compared to the others, in terms of mucus plugging. Nevertheless, current evidence indicates that, while not directly comparable, all four biologic drugs (benralizumab, tezepelumab, dupilumab, omalizumab) tend to decrease mucus plugs score as indicated by CT lung scans.

As mucus obstruction is increasingly recognized as one of the contributing factors to asthma severity, further studies are urgently needed to address several aspects, which may impact clinical outcomes. One important topic refers to the objective evaluation of the number and size of mucus plugs, as presented on thorax CT scans, which would allow the accurate comparison of their changes. To this direction, the standardization of a bronchopulmonary segment-based scoring system is needed, as it would facilitate its widespread application in clinical practice, resulting to a better characterization of this clinical phenotype. Moreover, literature indicate that mucus plugs are associated with worse asthma symptoms and severity10,22,23,29; however, there are no data regarding the impact of mucus plugs on the long-term prognosis of patients with poorly controlled asthma, and this is a question that needs to be addressed in long-term cohort studies in the future. Finally, the most important clinical question relates to the treatment efficacy of biologic agents. For this, prospective, placebo-controlled clinical trials with head-to-head comparisons are urgently needed to indicate whether there is an optimal choice for severe asthma patients with persistent mucus plugs.

Strengths and limitations

This narrative review is strengthened by its broad scope covering biologics and mucus plugging, irrespectively of the study protocol or date of publication, in an attempt summarize all current knowledge on the subject. However, due to the paucity of randomized controlled trials on the effect of biologics on mucus plugging, the small sample sizes and the variety of observation periods do not allow for safe statistical comparisons to be conducted. Moreover, although there are sufficient data to support that certain asthma phenotypes are more prone to mucus plugging, we did not identify data to support which patient subgroup may respond better to biologic treatments, which is another limitation of this review. Finally, as this was a narrative review, no formal risk of bias assessment or quality appraisal of included studies was performed. Future systematic reviews are hence warranted.

CONCLUSION

While research is expanding to understand the role of mucus plugging in the pathogenesis of asthma, recent evidence suggests that asthma patients with mucus plugs might be at risk of more frequent exacerbations and rapid decline in lung function. Additionally, as the relationship between mucins and T2 high inflammation pathway is not yet fully clarified, a mucoregulatory agent is not a reality, at least not for now. Using the novel MDCT mucus plug score, currently approved biologic agents have provided promising evidence to decrease mucus plugging in patients with poorly controlled asthma, as highlighted in the limited but valuable literature. Encouragingly, unplugging the airways through strategies that target mucus plugging in clinical practice may help us ‘unravel’ the future in the management of the disease in the era of biological therapies.