INTRODUCTION

Behçet’s disease (BD) is an inflammatory disorder, characterized by relapsing and remitting vasculitis, affecting blood vessels of all sizes1. Its clinical manifestations are diverse, often involving multiple organ systems, with common presentations including mucocutaneous and urogenital ulcers as well as ocular involvement2. Cardiovascular complications, though less frequent, significantly impact morbidity3. Pericarditis is the most common cardiac manifestation, but rarer complications such as myocardial infarction, myocarditis, and intracardiac thrombus have been documented4. Similarly, pulmonary artery thrombosis and aneurysms represent severe vascular complications, often leading to infarction or hemorrhage3.

This report describes a young male with no prior medical history who presented with pleuritic chest pain, accompanied by blood-streaked sputum, and subsequent findings of RV thrombus and pulmonary artery thrombosis, ultimately diagnosed as BD. The case highlights the diagnostic challenges and therapeutic strategies required to manage these rare manifestations effectively.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 21-year-old male, with no significant past medical history or regular medication use, presented to our center with a two-month history of chills, fatigue, and malaise, followed by four weeks of exertional dyspnea, dry cough, and intermittent hemoptysis. He had been diagnosed with pneumonia at an external facility two weeks prior, where a chest X-ray had shown left lower lobe consolidation. He was treated with ceftriaxone (IV, 1 g once daily for 5 days) and oral azithromycin (500 mg on day 1, followed by 250 mg/day for 4 days) for presumed pneumonia, but his symptoms persisted. At that time, a non-contrast chest CT was performed, showing bilateral consolidations predominantly in the lower lobes. On admission, he reported left-sided pleuritic chest pain. He denied unintentional weight loss, palpitations, sore throat, night sweats, or myalgia, and had no history of smoking, sick contacts, recent travel, or environmental exposures.

Physical examination revealed a temperature of 36.8°C, blood pressure of 125/73 mmHg, heart rate of 101 beats/min, respiratory rate of 18 breaths/min, and oxygen saturation of 94% on room air. Pulmonary and cardiac examinations were unremarkable, with no crackles, wheezing, or peripheral edema. An electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm without ischemic changes. Laboratory results showed hemoglobin 12.8 g/dL, WBC 5800/mm³ (neutrophils 68%), C-reactive protein (CRP) 54 mg/L, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 10 mm/h, with normal liver and renal function. Procalcitonin (PCT) level was not significantly elevated, measured at 0.1 ng/mL.

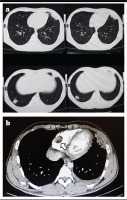

Multiple areas of consolidation were noted on CT, with no significant interval changes compared to prior imaging (Figure 1a). Lower limb venous Doppler was not performed due to the absence of clinical signs suggestive of deep vein thrombosis, such as leg swelling or pain. But considering the patient’s recent hospitalization, ongoing tachycardia, and hemoptysis, along with a Wells score indicating a high likelihood of pulmonary embolism, a CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) was performed to evaluate for possible thromboembolic events. CTPA identified filling defects in the segmental branches of the pulmonary arteries as well as in the right ventricle (RV) (Figure 1b). Additionally, multiple areas of consolidation were noted, with no significant interval changes compared to prior imaging.

Figure 1

a) Chest CT (axial view) showing bilateral patchy subpleural consolidations in the lingula and lower lobes, consistent with vasculitis-related inflammation; b) CTPA (axial view) demonstrating filling defects in segmental and subsegmental pulmonary artery branches bilaterally and a thrombus in the right ventricle (arrow)

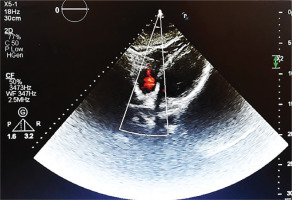

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) revealed a 2.8×2.2 cm partially mobile mass attached to the RV free wall, without involvement of the tricuspid valve. The mass demonstrated antegrade flow, supporting a thrombus rather than valvular vegetation. Cardiac function was preserved, with an ejection fraction of 55%, no regional wall motion abnormalities, and normal diastolic filling velocities, suggesting that the thrombus was primarily related to vasculitis rather than underlying cardiac dysfunction (Figure 2). Consecutive sets of blood cultures were obtained to rule out infective endocarditis, all of which yielded negative results. Rheumatoid factor (RF), viral serologies (e.g. HIV, hepatitis) and antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) diagnostic panel (e.g. lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, antibodies, and anti-beta-2 glycoprotein 1 antibodies) were also negative. Differential diagnoses for the RV mass included intracardiac thrombus secondary to BD-related vasculitis, non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE), and embolization from lower limb thrombi. Given negative blood cultures, absence of malignancy markers, and no clinical evidence of deep vein thrombosis, vasculitis-related thrombus was considered most likely. However, NBTE and thrombus embolization remain plausible and are discussed further in the Discussion section. Treatment was initiated with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH; enoxaparin 1 mg/kg twice daily) for suspected thrombus. Although the ESR was low (10 mm/h), this may reflect individual variation in inflammatory response. It may also have been attributable to the empiric antibiotics given during the prior hospitalization.

Figure 2

Transthoracic echocardiogram (four-chamber view) revealing a 2.8×2.2 cm irregular, mobile mass attached to the RV free wall

On day 3 of anticoagulation, the patient developed painful buccal ulcers, followed by a scrotal ulcer. He recalled a history of recurrent oral ulcers resolving spontaneously but denied prior genital lesions. Additional workup revealed HLA-B5 and B51 positivity, a positive pathergy test, and no ocular or neurological abnormalities (confirmed by brain CT and ophthalmologic evaluation). Based on the International Criteria for Behçet’s Disease (ICBD) (recurrent oral aphthosis: 2 points and genital aphthosis: 2 points) he scored four points, confirming BD5.

Management was escalated with intravenous cyclophosphamide (1 g/month), oral prednisone (1 mg/kg/day), and continued anticoagulation. LMWH was bridged to warfarin (5 mg once daily) after 5 days. Serial TTE at one and two months showed progressive reduction and complete resolution of the RV thrombus, respectively, with no recurrence of pulmonary symptoms. Follow-up CT of the lungs demonstrated resolution of pulmonary consolidations and no new lesions (Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

Behçet’s disease (BD) is a type of systemic vasculitis that clinically affects various organs and has no established specific causes1. Its prevalence is highest along the Silk Route, with a strong genetic link to HLA-B51, though this marker is not diagnostic6. The most common presentation includes recurrent oral and genital ulcers, along with ocular involvement such as uveitis. It can also manifest through gastrointestinal, central nervous system, cardiovascular, and pulmonary involvement, even as the first clinical presentation1,3,4.

Pulmonary involvement occurs in 10–40% of BD patients, with vascular complications (e.g. pulmonary artery thrombosis, aneurysms) often presenting early7,8. These may lead to hemorrhage, infarction, or atelectasis, while parenchymal changes reflect vasculitis-induced inflammation. Various lung parenchymal changes have been reported in Behçet’s disease patients. Including subpleural, and ill-defined ground glass opacities. Similar radiological features have been reported in cases of secondary eosinophilic pneumonia and organizing pneumonia associated with BD. Moreover, pulmonary vessel inflammation may contribute to the development of pneumonia and the formation of pleural nodules9-11.

In this case, bilateral consolidations were attributed to BD-related vasculitis, supported by their association with pulmonary artery thrombosis and the absence of eosinophilia or malignancy markers. Cardiac involvement, reported in 7–46% of cases, typically includes pericarditis or aortic aneurysms, but RV thrombus is exceedingly rare. The coexistence of RV thrombus and pulmonary artery thrombosis in this patient underscores BD’s prothrombotic nature, driven by endothelial injury and inflammation rather than classic hypercoagulability. This explains the limited efficacy of anticoagulation alone, necessitating immunosuppression3,12. In terms of management, corticosteroids remain the primary treatment for acute inflammation, often combined with immunosuppressants such as cyclophosphamide or azathioprine13. In our case, the initiation of intravenous cyclophosphamide was essential, given the severity of the patient’s condition.

Although anticoagulation is often necessary in patients with large intracardiac or pulmonary thrombi, it carries significant risks, particularly in the presence of pulmonary artery aneurysms, due to the potential for life-threatening bleeding14. Therefore, a balanced therapeutic approach, combining anticoagulation and immunosuppression, is essential for optimal outcomes. Colchicine was not initially included as the treatment focused on anticoagulation for thrombus resolution. However, its addition could be considered for managing systemic inflammation, as supported by prior studies15.

Complete thrombus resolution within two months highlights the efficacy of this approach, though anticoagulation risks (e.g. bleeding with occult aneurysms) were mitigated by imaging follow-up.

Regular monitoring through echocardiography and imaging is crucial for evaluating treatment response and preventing relapses6. A multidisciplinary approach integrating rheumatology, cardiology, and pulmonology is essential for tailored management and monitoring2,3.

CONCLUSION

This report describes a rare case of Behçet’s disease with right ventricular thrombus and pulmonary artery thrombosis. Its strength lies in long-term follow-up showing complete thrombus resolution, highlighting the effectiveness of combined immunosuppressive and anticoagulant therapy. The patient reported satisfaction with the treatment and improvement in symptoms. Informed consent for publication of this case was obtained from the patient. These findings emphasize the importance of early recognition and comprehensive management in patients with atypical thrombotic events.