INTRODUCTION

The hallmark of Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a prevalent lung condition globally, is a steadily increasing restriction of airflow1. COPD has a high and growing economic and social cost. In 2030, COPD will rank fourth in terms of causes of death and seventh in terms of disability-adjusted life years2. The burden should be attributed to everyday symptoms, including coughing, sputum production, and chronic and worsening dyspnea, which limit activities and eventually make it impossible for COPD patients to work and take care of themselves3. Exercise training, which is a key part of a pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) program, can help with some of these characteristics4.

A multidisciplinary team conducts a complete intervention as part of the evidence-based, non-pharmacological treatment known as PR5. It covers breathing exercises, mental health assistance, physical training, and dietary guidance. Researchers have been developing various ways to enhance the rehabilitation process from a clinical and financial perspective ever since new technologies were introduced6. Virtual reality (VR) is a potent tool in these solutions for enhancing fitness training, enabling customized treatments, performance tracking, and quantitative evaluation, as well as integrating sensors and external devices7,8.

The potential of VR in rehabilitation extends beyond COPD. Studies have shown positive impacts on motor function and balance in patients with neurological conditions like stroke and Parkinson’s disease9,10. VR’s ability to create safe and engaging environments can be particularly beneficial for phobias and anxiety disorders, allowing for controlled exposure therapy11. Additionally, VR offers advantages like customization of difficulty levels, real-time feedback, and data collection for therapists to monitor progress objectively12. However, challenges also exist. The initial cost of VR equipment can be high, limiting accessibility13. Potential side effects like cybersickness (nausea, dizziness) can occur in some users14.

COPD is a progressive disease with significant economic and social burdens. PR is a cornerstone of COPD management, but adherence and accessibility can be limitations. Virtual Reality (VR) presents a promising tool to enhance PR by offering engaging environments, personalized training, and real-time feedback. While VR holds promise in other rehabilitation areas, its application in COPD requires further investigation. The present systematic review and meta-analysis aim to synthesize the current evidence on the impact of VR on various aspects of COPD rehabilitation. By analyzing the existing research, a comprehensive understanding of VR’s effectiveness in improving exercise capacity, functional outcomes, and quality of life in COPD patients was assessed. This will ultimately inform clinical practice and guide future research directions for VR-based interventions in COPD management.

METHODS

Data sources and search strategy

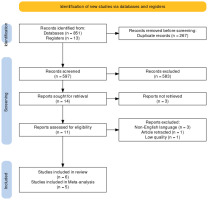

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed in the conduct and reporting of this study (Supplementary file). The search was applied in Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Embase, as well as the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) and Clinicaltrials.gov. Our search covered all studies without time limitation until December 2024, and the details of the searches are available in the Supplementary file. The systematic review protocol has been registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews under registration number CRD42024493732.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were performed with the aid of the PICO structure, based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that included: (P) COPD patients older than 18 years old; (I) who received VR training (VR or video games) as an intervention; (C) comparing the traditional rehabilitation method, with all noted outcomes included (O). Articles with any other respiratory disease were excluded. Also, articles with no full-text availability and studies with low-quality assessment scores were excluded after the screening phase. Our PICO question was: ‘Do the studies confirm that the extension of Virtual Reality to standard rehabilitation improves lung function in patients with COPD?’.

Study selection and data extraction

Two blinded reviewers (NM and FM), independently, screened the titles and abstracts of all references retrieved in each database. When one of these authors selected an article during the inclusion phase based on the title and abstract, it was examined in detail if the full text was available. Also, the references of similar articles have been screened for comprehensive coverage. All disagreements were resolved by a third author (SRN). Data were independently gathered from each study by a pair of reviewers using the form (NM and FM). Any differences were settled through discussion or the input of an additional reviewer (MS). The form for data extraction encompassed the following categories:

Study identification: names of authors, publication year, country;

Methodology: design, number of participants;

Population: demographics of participants (age and gender), criteria for inclusion and exclusion (patients with COPD, etc.);

Intervention(s): type of intervention(s) and type of device(s) that were used;

Comparator(s): details of the control or comparative group if necessary;

Outcomes: measures of primary and secondary outcomes; and

Results: important findings that answer the research question (direction of study effects).

Risk of bias and certainty assessment

In assessing the quality of the studies included in this review, the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) quality assessment checklist was used to evaluate the risk of bias15. Two authors (FM and NM) independently assessed the risk of bias in each study using the JBI quality assessment checklist, and when required, a third reviewer (SRN) decided the disagreement. Each study was scrutinized across multiple domains such as bias, blindness, follow-up, measurement, analysis, and design.

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) framework was employed to perform a certainty assessment, facilitating the evaluation of the confidence in the synthesized findings. Two reviewers (FM and NM) rated each domain for each comparison separately and resolved discrepancies by a third reviewer (MS). Each comparison and outcome was rated as ‘high’, ‘moderate’, ‘low’, or ‘very low’, based on considerations of risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, publication bias, and imprecision.

Statistical analysis

Data from included studies were analyzed using pre- and post-intervention mean values along with their standard deviations (SD) for both treatment and control groups. The data extracted from the studies were categorized in a table and prepared for analysis based on common outcomes. For exercise capacity, the 6 Minute Walk Test (6MWT); for pulmonary function, forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1); for quality of life, the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ); and for dyspnea, the Transitional Dyspnea Index (TDI) and Medical Research Council (MRC) were evaluated.

To calculate the pooled effect sizes and 95% CIs, we used a random-effects model, given that these studies were conducted across a variety of settings and populations. The measure of effect was the standardized mean difference (SMD).

In addition to inspection of forest plots, heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistic. Values ranging from 0% to 24% indicate the absence of heterogeneity. Values between 25% and 49% are considered low heterogeneity, while values between 50% and 74% are considered moderate. Furthermore, values ≥75% are indicative of substantial heterogeneity16.

Forest plots were used to display the results of the analyses. Given the small number of studies in each meta-analysis, we could not reliably assess publication bias using a funnel plot. However, we conducted Egger’s regression test as an alternative, acknowledging its low statistical power when fewer than 10 studies are included in a meta-analysis. Statistical analysis was conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) v3. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Search results and study characteristics

A total of 597 articles, after removing duplicates, were screened by title, abstract, and keywords. Fourteen articles were checked for full-text availability, and then the full text of 13 articles was assessed for other eligibility criteria. Five studies were excluded due to retraction by the author (n=1), non-English full text (n=3), and low-quality assessment (n=1); with the excluded studies noted in the Supplementary file. Finally, six studies were included in the review and 5 of them were used for meta-analyze as noted in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1).

The included studies encompassed a total of 278 participants, with sample sizes ranging from 20 to 100. The information regarding the studies17-22 included in the research is presented in Table 1. This table provides a detailed summary of the characteristics of each study, including factors such as gender, age, the number of participants, type of intervention, and methodology. It is important to note that all of the studies reported no negative effects in their conclusions. Detailed information about the interventions and comparators linked to each study in this review, especially regarding additional characteristics, individual results and outcomes, and adherence to the programs, is carefully organized in a table format and explained in the Supplementary file.

Table 1

Basic characteristics of the studies included in this systematic review

| Authors Year | Country | Design | Gender (n) (M/F) | Mean age (years) (M/F) | Sample size | Intervention | Outcome | Meta-analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu et al.17 2021 | China | RCT | EG: 40/10 CG: 38/12 | EG: 74.6/75.3 CG: 73.6/76.3 | EG: 50 CG: 50 | Bio Master | FEV1 6MWT CAT | Yes |

| Rutkowski et al.19 2021 | Poland | RCT | EG: 4/21 CG: 5/20 | EG: 64.4/5.7 CG: 67.6/9.4 | EG: 25 CG: 25 | VR TierOne device | FEV1 6MWT HADS-D HADS-A | Yes |

| Rutkowski et al.18 2020 | Poland | RCT | EG: 17/17 CG: 10/24 | EG: 60.4/4.2 CG: 62.1/2.9 | EG: 34 CG: 34 | Xbox 360 console | 6MWT Physical fitness | No |

| Rutkowski et al.22 2019 | Poland | RCT | EG: 17/17 CG: 18/16 | EG: 60.5/4.3 CG: 62.1/2.9 | EG: 34 CG: 34 | Xbox 360 console | 6MWT Physical fitness | Yes |

| Sutanto et al.21 2019 | Indonesia | RCT | EG: 9/1 CG: 10/0 | EG: 65.1/7.5 CG: 656/4.7 | EG: 10 CG: 10 | Wii Fit | 6MWT SGRQ TDI BODE MRC | Yes |

| Mazzoleni et al.20 2014 | Italy | RCT | NA | EG: 68.9/11 CG: 73.5/9.2 | EG: 20 CG: 20 | Wii Fit Plus | 6MWT SGRQ TDI STAI BDEI MRC | Yes |

[i] M: males. F: females. EG: experimental group. CG: control group. 6MWT: 6-minute walking test. BEDI: beck depression inventory. BODE: body max index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index. CAT: COPD assessment test. FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 second. FEV1/FVC: forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity. HADS-D: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale - depression subscale. HADS-A: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale - anxiety subscale. MRC: Medical Research Council. SGRQ: St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. STAI: State and Trait Anxiety Inventory.

Risk of bias and certainty assessment

The risk of bias assessment revealed that some studies were at high risk of bias for several domains. Due to weakness in blinding, a substantial risk that is commonly referred to as performance bias was observed for all the included RCTs. The low risk of selection bias has been detected in most studies. Overall, all studies had almost the same quality. The minimum score for including articles was 7 out of 13. The risk of bias for each study is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

Risk of bias assessment for the included studies

| Study | Type of Bias | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection | Allocation concealment | Baseline comparability | Performance | Performance | Detection | Performance | Attrition | Analytic | Measurement | Measurement | Statistical analysis | Other | Score (max 13) | |

| Liu et al.17 2021 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 7 |

| Rutkowski et al.19 2021 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✕ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 9 |

| Rutkowski et al.18 2020 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✕ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 9 |

| Rutkowski et al.22 2019 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 7 |

| Sutanto et al.21 2019 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | 7 |

| Mazzoleni et al.20 2014 | ✔ | ✕ | ✔ | ✔ | ? | ? | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✕ | 7 |

Egger’s test was performed to assess potential publication bias. The results showed an intercept of -2.40 (95% CI: -12.22–7.43, p=0.40), indicating no statistically significant evidence of asymmetry.

The certainty of evidence regarding outcomes was assessed and rated from high to low. This evaluation was downgraded due to serious and very serious inconsistencies observed in the FEV1 and TDI analysis, respectively, which stemmed from heterogeneity across the included studies. Additionally, serious indirectness and imprecision were noted in the SGRQ analysis. The rationale for these decisions across each domain is summarized in the Supplementary file.

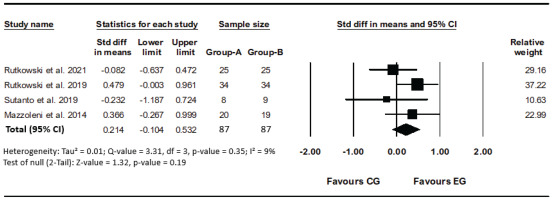

Comparison of 6MWT between VR training and traditional training

All six studies reported 6MWT as an outcome, of which only four studies were eligible for 6MWT analysis19-22. One study reported significant results during the intervention; due to the unavailability of values, it was not possible to include it in the meta-analysis17. Another study reported the results of its previous publication and to prevent any bias, it was excluded from meta-analysis. When this study was included in a meta-analysis, the I² statistics increased to 94% (p<0.001) and indicated substantial heterogeneity18. Comparing the data analysis of four studies that show no heterogeneity (I²=9%, p=0.35)19-22. The use of VR compared to the common method of pulmonary rehabilitation does not determine a significant difference and does not have much effect (SMD=0.21; 95% CI: -0.10–0.53, p=0.19; GRADE: High) (Figure 2).

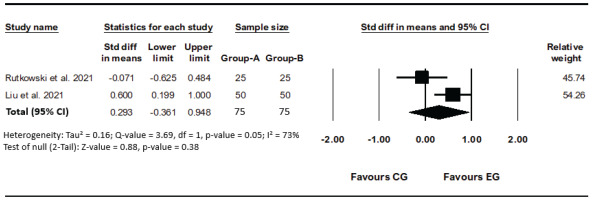

Comparison of FEV1 between VR training and traditional training

In two studies FEV1 has been evaluated and moderate heterogeneity was detected (I²=73%, p=0.05)17,19. The results obtained from the analysis of the conducted studies show that there is no significant difference between groups (SMD=0.29; 95% CI: -0.36–0.95, p=0.38; GRADE: Moderate) (Figure 3).

Comparison of SGRQ between VR training and traditional training

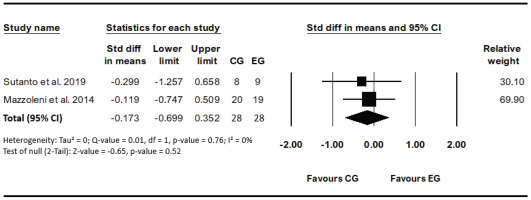

Two studies evaluated the effect of VR-based rehabilitation compared traditional method on SGRQ to assess the quality-of-life score before and after the interventions20,21. No heterogeneity (I²=0%, p=0.75) was detected between studies. The results revealed that the VR intervention effects were not significant compared to other interventions (SMD= -0.17; 95% CI: -0.70–0.35, p=0.52; GRADE: Low) (Figure 4).

Comparison of TDI between VR training and traditional training

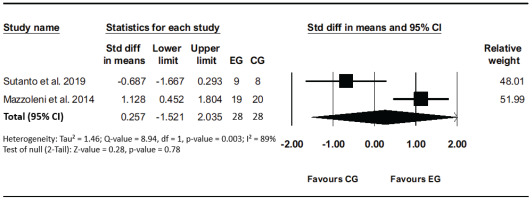

Two studies evaluated the effect of VR-based rehabilitation compared to the traditional method on TDI to assess the Transitional Dyspnea Index before and after the interventions. High heterogeneity (I²=89%, p=0.003) was detected between studies. The results revealed that the VR intervention effects were not significant compared to other interventions (SMD=0.26; 95% CI: 1.52–2.04, p=0.78; GRADE: Low) (Figure 5).

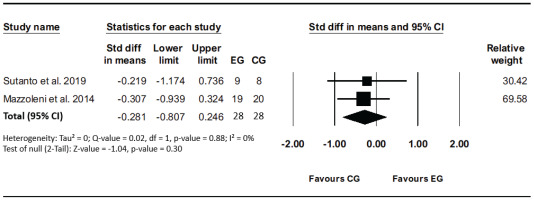

Comparison of MRC between VR training and traditional training

Two studies evaluated the effect of VR-based rehabilitation compared to the traditional method on the Medical Research Council (MRC) to assess the degree of baseline functional disability due to dyspnea before and after the interventions. No heterogeneity (I²=0%, p=0.88) was detected between studies. The results revealed that the VR intervention effects were not significant compared to other interventions (SMD= -0.28; 95% CI: -0.80–0.25, p=0.30; GRADE: Moderate) (Figure 6).

Cost-effectiveness of VR intervention

Three studies included in this review addressed the cost implications of the new intervention compared to the traditional method. One study explored the potential for delivering the new intervention more cost-effectively by utilizing lower cost equipment22. Two other studies highlighted the increased costs associated with implementing the new intervention when compared to traditional methods. These studies questioned the overall cost-effectiveness of the new intervention, particularly considering the statistically modest clinical improvements observed in their findings20,21.

DISCUSSION

The present systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the efficacy of VR as a rehabilitative intervention for patients with COPD. The results suggest that while VR interventions are safe and feasible23, their superiority over traditional rehabilitation methods in improving exercise capacity, pulmonary function, and quality of life is not statistically significant.

The lack of a significant difference in the 6MWT outcomes between VR and traditional training is noteworthy. This finding aligns with the individual study results, which reported no negative effects but also failed to demonstrate a clear advantage of VR. It is possible that the immersive nature of VR may offer a more engaging experience for patients, potentially leading to better adherence to rehabilitation programs24. However, the current evidence does not support a definitive conclusion that VR leads to improved physical outcomes. It should be noted that studies with a longer intervention period did not provide more promising results, contrary to expectations17,21.

Regarding pulmonary function, as measured by FEV1, the moderate heterogeneity observed across studies suggests variability in the VR interventions’ effectiveness. This could be attributed to differences in VR equipment, program design, or patient characteristics and future research must be conducted using the same standards and protocols25. The absence of a significant effect on FEV1 indicates that while VR may serve as an alternative to traditional methods, it does not necessarily enhance pulmonary function beyond what is achieved with conventional rehabilitation.

The analysis of the SGRQ scores, which assess the quality of life, revealed no significant differences between VR-based and traditional rehabilitation. This outcome suggests that the impact of VR on the subjective experience of patients with

COPD is similar to that of standard care. The analysis of TDI and MRC did not suggest any advantages of VR intervention, and it is concluded that no improvement in dyspnea can be achieved compared to the traditional intervention. It should be noted that in COPD patients, dyspnea may arise from various factors26.

The cost-effectiveness of VR interventions remains uncertain. While one study suggested the potential for lower cost VR equipment, others highlighted increased costs without proportional clinical benefits. Some studies support the cost-effectiveness of different tele-rehabilitation methods27. The economic implications and cost-effectiveness of VR in COPD rehabilitation warrant further investigation, particularly in light of the modest clinical improvements observed.

Limitations

A limitation of the included studies is the lack of uniformity in the outcomes examined in them; it is suggested that future studies focus more on outcomes. Another limitation is the small sample size of patients in most studies, which may have affected the statistical differences observed between the two interventions. Additionally, the studies have not consistently reported the same outcomes, and some outcomes were not presented in a manner suitable for meta-analysis. Furthermore, a non-inferiority analysis was considered but not performed due to challenges in establishing well-justified a priori non-inferiority margins for the included outcomes based on current evidence.

To mention other limitations, it is important to note that publication bias detection methods are unreliable with fewer than 10 studies. As such, any conclusions regarding publication bias should be interpreted cautiously. The discussion of limitations should also include considerations of cost-effectiveness, as well as the challenges associated with the exclusion of certain non-English studies from the analysis. These factors may potentially influence the comprehensiveness and applicability of the findings.

CONCLUSIONS

VR represents a novel approach to COPD rehabilitation with the potential to enhance patient engagement. However, the current evidence, limited by small sample sizes and likely insufficient statistical power, heterogeneity across studies, lack of uniformity in outcomes and potential for publication bias, does not suggest it is more effective than traditional methods in improving exercise capacity, pulmonary function, or quality of life. Future research should focus on addressing these limitations by including larger sample sizes, using uniform outcome measures, and assessing long-term outcomes and cost-effectiveness, in order to identify specific patient populations that may benefit most from VR and optimizing VR program design.