INTRODUCTION

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a major cause of hospital admissions, workforce loss, and mortality globally. Despite the widespread use of antibiotics and national immunization policies that have reduced mortality from infectious diseases, CAP remains a leading cause of high morbidity and mortality1,2.

In most patients diagnosed with CAP, the causative pathogen cannot be identified, even with extensive microbiological testing in laboratory settings3,4. Studies conducted in Türkiye involving CAP cases show that the rate of identifying etiological agents ranges from 21% to 62.8%. However, retrospective studies using routine diagnostic methods indicate that the rate of identifying etiological agents averages around 22–35.8%2,5.

It is well established that delays in treatment for patients with pneumonia significantly increase morbidity and mortality. Although identifying the causative agent is ideal, culture and pathogen identification procedures take time, which necessitates the early initiation of empirical antibiotic therapy6,7.

The aim of our study is to evaluate the sputum culture results of patients hospitalized with a diagnosis of CAP and to investigate the relationship between the etiologic agents and the duration of hospitalization. We hypothesized that discordance between empirical therapy and culture results, as well as the presence of specific pathogens, would prolong hospitalization.

METHODS

Study group

Data from patients hospitalized with a diagnosis of CAP in the Chest Diseases Clinic of Düzce University Medical Faculty Hospital between October 2022 and November 2023 were evaluated in this cross-sectional study. Pneumonia was diagnosed based on a combination of clinical and radiological findings. Before inclusion, participants were informed about the content, purpose, and procedures of the study, and their written consent was obtained. Patients included in the study were those aged >18 years and diagnosed with CAP. Exclusion criteria consisted of cases of hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia.

For the included patients, complete blood count parameters, biochemical and microbiological examinations were recorded from the hospital database. Sputum samples were collected in sterile containers and transported to the clinical microbiology laboratory immediately. Processing was initiated within 2 hours of collection to ensure sample integrity. Before bacterial culture, all sputum samples were evaluated for quality using Bartlett’s scoring. Samples deemed suitable for examination were inoculated onto 5% sheep blood agar (Condolab, Madrid, Spain), Eosin Methylene Blue agar, and chocolate agar (Condolab, Madrid, Spain), and then incubated at 35–37°C for 48 hours. After incubation, isolates showing growth were identified, and antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed using the Vitek 2 automated system (bioMérieux, France) and conventional methods8,9.

Demographic characteristics of the patients, complete blood count parameters, biochemical analysis results, microbiological samples, CURB-65 (confusion, urea, respiratory rate, blood pressure, ≥65 years), and pneumonia severity index (PSI) data were recorded using a data preparation form. Antibiotics initially administered to patients were classified into three groups: Group 1 (initial antibiotics), Group 2 (antibiotics added or changed later), and Group 3 (third change).

Ethics

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The ethical approval was obtained from the Düzce University Faculty of Medicine NonInvasive Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Date: 07.10.2022 and decision no: 2022/191).

Statistical analysis

While the independent sample t-test was used for group comparisons of quantitative variables that met the parametric test assumptions (normality, homogeneity of variance, etc.), Mann-Whitney U and median tests were used when these assumptions were not met. Relationships between categorical variables were analyzed using Pearson chi-squared, and Fisher Freeman Halton tests (post hoc Bonferroni corrected z-test). A non-parametric multiple linear regression analysis with forward variable selection algorithm was applied to simultaneously examine all factors considered to affect the dependent variable. Statistical evaluations were performed using SPSS 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 4.1.1 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was defined as a p<0.05.

RESULTS

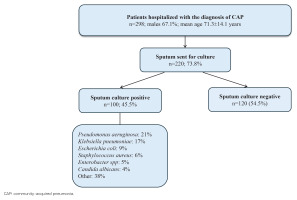

A total of 298 patients with a mean age of 71.3 ± 14.1 years, 67.1% male, were involved in the study. The study flow chart, illustrating patient enrollment and exclusion, is presented in Figure 1. Most patients (96%) had additional comorbidities. Malignancy was present in 26.2% of patients (n=78), and lymphopenia was observed in a significant portion of the patients (Table 1). These variables were specifically analyzed in relation to hospitalization outcomes. The smoking history data are also presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Characteristics and comorbidities of patients* hospitalized with CAP at Düzce University Hospital, 2022–2023 (N=298)

Sputum culture samples were obtained from 73.8% (n=220) of the patients. Sputum cultures could not be obtained in the remaining 26% (n=78) of patients, primarily due to the inability to expectorate spontaneously (non-productive cough) or insufficient sample quality for valid microbiological assessment. Among those who provided culture samples, 45.5% (n=100) had positive results. Examination of the gram stain results of the patients from whom sputum culture samples were obtained revealed that 71.8% (n=158) had abundant PMNL (polymorphonuclear leukocytes). The acid-fast bacillus (AFB) result was negative in 93.6% of those who provided cultures. The microorganisms isolated from the purulent sputum samples identified by gram staining microscopy, and their respective frequencies among the 100 patients, were as follows: Pseudomonas aeruginosa in 21% (n=21), Klebsiella pneumoniae in 17% (n=17), Escherichia coli in 9% (n=9), Staphylococcus aureus in 6% (n=6), Enterobacter spp. in 5% (n=5), Candida albicans in 4%, and other bacteria in 38% (n=38). Table 2 shows the isolated pathogens.

Table 2

Distribution of microorganisms isolated from sputum cultures in patients with positive growth hospitalized with CAP at Düzce University Hospital, 2022–2023 (N=100)

A significant difference was found in terms of sex, duration of hospitalization, patient course, PSI, and CURB-65 risk scores according to the sputum culture results, excluding age, smoking status, and pack-years of smoking (p<0.05) (Table 3). Males with positive sputum cultures, those with a PSI risk score of 5, a CURB-65 risk score of 4, those referred, and those who died had significantly higher rates compared to those with negative sputum cultures. In contrast, females with positive results, those with a PSI risk score of 3, a CURB-65 risk score of 1, and those discharged, had significantly lower rates.

Table 3

Comparison of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics based on sputum culture results in patients hospitalized with CAP at Düzce University Hospital, 2022–2023 (N=220)

| Characteristics | Sputum culture | Estimate/OR (95% CI) | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| Sex | Female | 49 | 40.8 | 22 | 22 | - | 0.003a |

| Male | 71 | 59.2 | 78 | 78 | OR=2.4 (1.4-4.4) | ||

| Age (years)*# | 70 ± 14.2 72 ( 15.8) | 71.6 ± 15.6 73 (18) | 1.60 (-5.6-2.4) | 0.427c | |||

| Smoking status | Non-smoker | 57 | 47.5 | 38 | 38 | - | 0.058a |

| Smoker | 18 | 15 | 9 | 9 | |||

| Ex-smoker | 45 | 37.5 | 53 | 53 | |||

| Cigarette pack -years*# | 47.8 ± 29.5 45 (25) | 44.6 ± 19.3 40 (20) | 0 (-5-10) | 0.705d | |||

| Duration of ho spitalization (days)*# | 7.6 ± 3.4 7 (4) | 10.2 ± 5.3 9 (6) | -2 (-3 - -1) | <0.001d | |||

| PSI | 1 | 4 | 3.3 | 2 | 2 | OR=1.6 (1.2-2.1) | 0.001b |

| 2 | 20 | 16.7 | 13 | 13 | |||

| 3 | 29 | 24.2 | 8 | 8 | |||

| 4 | 55 | 45.8 | 51 | 51 | |||

| 5 | 12 | 10 | 26 | 26 | |||

| PSI*# | 3.4 ± 0.9 4 (1) | 3.9 ± 1 4 (1) | 0 (-1-0) | <0.001d | |||

| CURB-65 | 0 | 1 | 0.8 | 3 | 3 | OR=1.5 (1.1-2.1) | 0.038b |

| 1 | 54 | 45 | 29 | 29 | |||

| 2 | 57 | 47.5 | 53 | 53 | |||

| 3 | 5 | 4.2 | 5 | 5 | |||

| 4 | 2 | 1.7 | 8 | 8 | |||

| 5 | 1 | 0.8 | 2 | 2 | |||

| CURB-65*# | 1.6 ± 0.7 2 (1) | 1.9 ± 0.9 2 (1) | 0 (0-0) | 0.073e | |||

| Patient course | Discharged | 114 | 95 | 80 | 80 | 0.004b | |

| Referred | 3 | 2.5 | 9 | 9 | OR=4.3 (1.1-16.3) | ||

| Refusing treatment | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | - | ||

| Died | 3 | 2.5 | 10 | 10 | OR=4.8 (1.3-17.8) | ||

In the group with positive culture growth, the duration of hospitalization and PSI risk score were significantly higher compared to the group without culture growth (p<0.05) (Table 3). When examining the impact of comorbidities on the duration of hospitalization, there was no significant difference in duration of hospitalization in relation to the presence of comorbid conditions, except for the presence of CVD (p=0.030) and malignancy (p=0.039). We observed that patients requiring a modification to their initial antibiotic regimen (switching to Group 2 or Group 3) experienced significantly prolonged hospital stays. This finding, supported by our regression analysis, underscores the critical importance of selecting an appropriate initial empirical therapy. The delay inherent in identifying the pathogen and subsequently adjusting treatment likely contributes to this extended hospitalization duration.

In our study, potential confounding factors that could affect the relationship between the independent and dependent variables were examined. There was no prior confounding factor that could significantly influence either of the two. After the forward variable selection algorithm was applied, a non-parametric significant linear regression model was constructed in which each of the independent variables, ‘CURB-65, use of group 2 antibiotics, presence of lung malignancy, history of pneumonia, immobility, presence of lymphopenia’ which affect the dependent variable, ‘duration of hospitalization’, was significant (F=38.95, p<0.001) (Table 4). These factors explain 45% of the variance in the duration of hospitalization. According to this model, each one-unit increase in the CURB-65 risk score is associated with a 0.57-unit increase in the duration of hospitalization. Additionally, the duration of hospitalization increases by 7.43 units when a Group 2 antibiotic regimen is used, by 2.57 units in cases of immobility, by 1.43 units in the presence of lung malignancy, and by 0.71 units with a history of pneumonia. On the other hand, the duration of hospitalization decreases by 0.71 units when lymphopenia is present (Table 4).

Table 4

Nonparametric linear regression model of factors affecting duration of hospitalization in patients with CAP at Düzce University Hospital, 2022–2023 (N=298)

In our study, when examining the impact of isolated pathogens on the duration of hospitalization in patients with positive sputum cultures, there was no significant difference in terms of duration of hospitalization based on the presence of P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and S. aureus (p>0.05) (Table 5). However, the duration of hospitalization was significantly higher in patients with multiple bacterial isolates compared to those with single bacterial isolates (p=0.026) (Table 5). The mean duration of hospitalization was found to be 8.2 ± 4.5 days; 87.2% (n=260) of patients were discharged, while the mortality rate was 5.4% (n=16). Additionally, 1.3% of the patients (n=4) were discharged early at their own request, while 6% (n=18) were referred to another healthcare facility. However, their follow-up and care were not continued after being referred.

Table 5

Relationship between isolated pathogens and duration of hospitalization in culture-positive patients with CAP at Düzce University Hospital, 2022–2023 (N=100)

| Result | Duration of hospitalization (days) | Estimate (95 % CI ) | pa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Median | IQR | ||||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Negative (n=79) | 10.2 | 5.4 | 9 | 7 | 0 (-3-2) | 0.699 |

| Positive (n=21) | 10.4 | 5.3 | 10 | 5 | |||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Negative (n=83) | 10.3 | 5.4 | 9 | 6 | 1 (-2-3) | 0.593 |

| Positive (n=17) | 9.8 | 5.3 | 9 | 6 | |||

| Escherichia coli | Negative (n=91) | 10.1 | 5.3 | 9 | 6 | -1 (-5-3) | 0.612 |

| Positive (n=9) | 11.2 | 5.5 | 9 | 11 | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus | Negative (n=94) | 10.4 | 5.4 | 9 | 6 | 2 (-2-6) | 0.326 |

| Positive (n=6) | 8.0 | 3.9 | 7.5 | 7 | |||

| Enterobacter spp* | Negative (n=95) | 10.3 | 5.4 | 9 | 6 | - | - |

| Positive (n=5) | 9.8 | 2.8 | 9 | 3 | |||

| Candida albicans* | Negative (n=96) | 10.3 | 5.4 | 9 | 6 | - | - |

| Positive (n=4) | 7.8 | 1.3 | 8 | 1.5 | |||

| Single and multiple growth in sputum culture | Single (n=89) | 9.8 | 5.1 | 9 | 6 | -4 (-7-0) | 0.026 |

| Multiple (n=11) | 13.7 | 5.8 | 13 | 7 | |||

DISCUSSION

CAP remains a major public health challenge worldwide, with significant variability in pathogen isolation rates across different regions and populations. Studies conducted in our country involving CAP cases show that the rate of identifying etiological agents ranges from 21% to 62.8%10. In our study, only spontaneous sputum samples were collected, without the use of invasive procedures such as bronchoscopy. This methodological difference may partially explain the lower positivity rate observed in our study group. A significant portion of our patients were able to provide sputum samples, and 45.5% of these yielded positive culture results. In a study by Sever et al.11, the rate of etiological pathogen detection was reported as 77.8% in 72 CAP cases. These findings illustrate the wide variability in pathogen isolation rates in CAP cases across Türkiye. The fact that a large proportion of our patients were able to provide sputum samples is notable; however, the relatively low culture positivity rate highlights the ongoing challenges in accurately identifying etiological agents.

In addition to the overall positivity rate, the spectrum of isolated pathogens provides further insight into the microbiological landscape of CAP in our population. In our study, P. aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae were the most frequently isolated microorganisms, followed by E. coli and S. aureus. These findings highlight the broad diversity in the etiological agents of CAP. In comparison to previous studies, Ludlam et al.12 reported that S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis were the most frequently cultured microorganisms12, while Para et al.13 found S. pneumoniae in 30.5% of sputum cultures from 205 hospitalized patients. Likewise, Kurutepe et al.14 also observed S. pneumoniae as a prominent pathogen. The diversity of microorganisms isolated from CAP patients in our study underscores the wide range of potential pathogens involved and offers valuable insights for clinical decision-making regarding treatment strategies. However, broader-scale studies are needed to account for regional and population-based differences. Notably, our study revealed an unexpectedly high prevalence of P. aeruginosa, which warrants particular attention. Our study observed a higher prevalence of P. aeruginosa than typically seen in the empirical treatment regimen. This discrepancy suggests that initial antibiotic therapy may be insufficient for certain pathogens, especially with the emerging resistance patterns. We recommend that clinicians consider factors such as comorbidities, prior antibiotic use, and local resistance trends when selecting empirical treatment regimens. These findings raise important questions about the factors that might contribute to such variations in pathogen distribution.

Several factors could explain the differences in the frequency of bacterial pathogens observed in our study. First, previous antibiotic use and the development of resistance might contribute to these variations. Second, suboptimal conditions during sample collection, handling, and laboratory processing could affect the accuracy and reliability of the microorganism identification. Finally, our study only included hospitalized patients with moderate to severe pneumonia, unlike outpatient cases, which generally represent less severe infections. This may explain the higher pathogen isolation rates seen in our patients compared to outpatient populations.

In our study, we observed statistically significant differences in age, sex, smoking status, pack-years of smoking, duration of hospitalization, patient outcomes, and risk scores (PSI and CURB-65) based on sputum culture results. The group with positive sputum cultures demonstrated higher hospitalization duration and elevated PSI and CURB-65 risk scores compared to the group with negative cultures. These findings suggest that more severe clinical presentations, as reflected by higher PSI and CURB65 scores, are associated with positive sputum cultures and prolonged hospitalization.

The association between higher CURB-65 and PSI scores and increased hospitalization duration aligns with previous studies. For example, Snijders et al.15, in a cohort of 474 hospitalized patients, also found that those with positive sputum cultures had higher CURB-65 and PSI scores, and longer hospital stays were observed with increased risk scores. Similarly, Eshwara et al.16, in their study of 100 patients, found that although smoking status did not correlate with sputum culture positivity, the group with positive cultures had higher CURB-65 and PSI scores, further confirming the relationship between more severe disease and positive culture results. In a study by Tapan et al.17, higher CURB-65 and PSI scores were also associated with longer hospitalization. Our findings are consistent with these studies, reinforcing the idea that higher risk scores correlate with more severe disease and extended hospital stays.

When examining the effect of comorbidities on the duration of hospitalization, there was no significant difference in hospitalization duration related to the presence of additional diseases, except for the presence of CVD and malignancy. In a study by Şenol et al.18, patients without comorbid conditions had an average hospital stay of 5.8 days, while COPD, CVD, and diabetes mellitus were found to increase the duration of hospitalization. A study conducted in Taiwan reported that patients with CVD had a higher risk of CAP and this condition also affected the duration of hospitalization. Similarly, our study found that the presence of CVD was associated with a longer hospital stay19. In patients with malignancy, immunosuppression can develop due to the underlying primary disease and the resultant neutropenia from treatment. Similar to our study, the literature has shown that the incidence of CAP and the duration of hospitalization due to CAP are increased in these patients20.

In our study, empirical antibiotic therapy was initiated based on the patients’ risk profiles at the primary treatment level. For 53% (n=158) of the patients, the initial treatment consisted of ampicillin-sulbactam plus clarithromycin. Among the 120 patients with negative sputum cultures, only 13 required a change in antibiotic therapy. For these patients, the antibiotic regimen was adjusted to a more comprehensive and potent regimen than the initial one. Among the 100 patients with positive sputum cultures, 75 showed clinical improvement with the initial empirical treatment, indicating a clinical response to the therapy, regardless of the pathogen’s susceptibility. In cases requiring a change in the initial antibiotic regimen, the most commonly used therapy was piperacillin-tazobactam plus clarithromycin, accounting for 30.9% (n=13) of patients. Our study found that when modifications were made to the initial empirical treatment due to clinical non-response or sputum culture results, the duration of hospitalization increased. The change in antibiotic therapy extended the average duration of hospitalization by 7.4 days. We believe that careful consideration of all variables before starting empirical treatment may help reduce the duration of hospitalization. To improve empiric coverage, it may be useful to consider specific clinical factors such as comorbidities (e.g. diabetes, chronic lung disease), previous antibiotic use, and local resistance trends when selecting initial treatment regimens. These factors could help identify patients who may require broader spectrum antibiotics.

In our study, a non-parametric regression model examining factors affecting the duration of hospitalization (CURB-65 risk score, use of second-line antibiotics, presence of lung malignancy, history of pneumonia, immobility, lymphopenia) was found to be significant. These factors explained 45% of the variance in hospitalization duration. We observed that patients with positive sputum cultures had higher CURB-65 scores compared to those with negative cultures. Furthermore, the duration of hospitalization was notably longer in the culture-positive group, reflecting the clinical impact of identified pathogens. Our regression analysis indicated that increased CURB-65 risk scores, patient immobility, and the presence of lung malignancy were independent factors associated with prolonged hospitalization. A study by Tapan et al.17 also found that an increase in the CURB-65 risk score was associated with a longer hospital stay. In cases of patient immobility, the average duration of hospitalization increases by 2.5 days. A study by Hoheisel et al.21 found that immobility increased the hospital stay by 2.4 days. Another study conducted in Türkiye also reported that the duration of hospitalization for immobilized patients was longer compared to those who were not immobilized18. The presence of lung malignancy increases the average duration of hospitalization in our study population by 1.4 days.

It is well known that a history of pneumonia is a risk factor for CAP22. In our study, patients with a history of previous pneumonia had an average increase of 0.71 days in their duration of hospitalization compared to other patients. In our study, the presence of lymphopenia in patients was associated with a decrease of 0.71 days in the duration of hospitalization. However, literature data indicate that lymphopenia generally increases the duration of hospitalization. Cilioniz et al.23 found that lymphopenic patients had longer hospital stays and higher mortality rates. Similar findings were reported by Bermejo-Martin et al.24.

In our study, when examining the impact of isolated pathogens on the duration of hospitalization in patients with positive sputum cultures, there was no significant difference in hospitalization duration among those with P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and S. aureus. However, patients with multiple bacterial pathogens had a significantly longer hospital stay compared to those with a single bacterial pathogen. In a study by Şenol et al.18 involving 400 hospitalized patients, it was found that the presence of S. pneumoniae in sputum cultures increased the duration of hospitalization. Another study concluded that patients with sputum cultures positive for P. aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, and S.aureus had longer hospital stays25.

In a study by Ludlam et al.12, the presence of pathogen growth in sputum cultures was associated with an average increase of 2.5 days in hospitalization duration. Their findings also indicated that infections caused by P. aeruginosa, H. influenzae, and S. aureus were linked to longer hospital stays compared to other bacterial agents12. Similarly, Para et al.13 reported that the most frequently isolated pathogens were P. aeruginosa (31.5%), S. aureus (25.9%), and S. pneumoniae (11.9%). While P. aeruginosa was significantly associated with prolonged hospitalization in their cohort, no such association was observed for the other pathogens13. In contrast, our study did not reveal any statistically significant differences in hospitalization duration based on the specific pathogen isolated.

Among the patients with CAP who were hospitalized in our study, 87.2% were discharged, while the mortality rate was 5.4%. In a study by Latif et al.26, which analyzed data from 17425 patients, the discharge rate for the general population was 86.2%, and the mortality rate was 5.6%. Another study conducted in Türkiye reported a discharge rate of 91.4% and a mortality rate of 3.3%27.

Limitations

The limitations of our study include its single-center design and the relatively small sample size. Future research could involve multi-center studies with larger patient populations to thoroughly examine the factors affecting the duration of hospitalization. Moreover, the study design (cross-sectional) does not allow causal inference, and the results may not be generalizable to other populations.

Implications

The demographic characteristics of CAP patients in Türkiye are similar to those of the global CAP population. The presence of comorbid conditions influences the duration of hospitalization. It is crucial to review all risk factors at the start of treatment and to initiate appropriate empirical antibiotic therapy. Properly administered treatment at the appropriate location improves treatment success and reduces hospital stay, treatment costs, mortality, and morbidity rates.

In our study, the most frequently isolated microorganisms in sputum cultures were P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, and E coli. Unlike global trends where S. pneumoniae is traditionally the most common cause of CAP, our results showed a predominance of gram-negative pathogens. Several factors may explain this discrepancy. First, our study population consisted of hospitalized patients in a tertiary care chest clinic, many of whom had comorbidities such as malignancy and chronic lung disease – conditions known to predispose patients to opportunistic gram-negative infections. Second, standard culture methods have relatively low sensitivity for detecting fastidious organisms such as S. pneumoniae or atypical pathogens, particularly when compared with PCRbased techniques. Third, prior outpatient antibiotic use may have suppressed susceptible organisms, leading to an overrepresentation of resistant gram-negative bacteria in culture results.

Although our study did not demonstrate a significant association between isolated microorganisms and length of hospital stay, the literature suggests that culture results can influence hospitalization duration both globally and in Türkiye. In our cohort, 45.5% of hospitalized CAP patients had positive sputum cultures. Notably, hospitalization duration was longer in patients with multiple causative agents compared to those with a single pathogen. These findings indicate that sputum culture results should be carefully evaluated, and treatment modifications should be approached cautiously.

Overall, our results may guide future clinical research by supporting the development of patient-specific risk assessment tools and tailored treatment strategies aimed at improving hospitalization outcomes in similar patient populations. Further studies are needed to better define optimal indicators for guiding empiric therapy and to evaluate the impact of local resistance patterns and comorbidities on the selection of effective empirical treatment regimens.

CONCLUSIONS

Among hospitalized CAP patients with high comorbidity burdens, gram-negative pathogens and poly-microbial growth are frequently observed and are associated with prolonged hospitalization. Clinicians managing similar high-risk populations should consider these pathogens when determining empirical treatment strategies.