INTRODUCTION

The emergence of drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) strains that are refractory to the standard combination therapy is a worldwide concern1. Little progress was made with anti-TB agents for 40 years prior to the 2010s2. Only rifapentine (a long-acting rifamycin) was introduced in 19983. The effectiveness of the available therapy against resistant strains during this time was limited. Recently, however, three new anti-TB drugs have been introduced: bedaquiline (BDQ) in 2012, delamanid (DLM) in 2014, and pretomanid (Pa) in 20194,5. They are now part of the treatment regimen (for 6 or 9 months or longer) to treat multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB)6.

In addition to the standard of care, BDQ, DLM, and Pa are often used individually or in combination, and despite the encouraging evidence of the use of these drugs on DR-TB strains, they have been linked to cardiotoxic risks, specifically an effect on corrected QT interval (QTc). A cohort study reported that QTc prolongation was the most frequent treatment emergent adverse event (TEAE) (1.5%) among patients who received BDQ, leading to either discontinuation of the medication or withdrawal7. A systematic review reported that Pa was also associated with QTc prolongation, and the risk was even higher when combined with BDQ8. Li et al.9 studied concentration-QTc modeling on Pa alone and on the combination BDQ-Pa-linezolid (BPaL) regimen and found a mean change in QTc of 9.1 milliseconds (ms) and 13.6 ms, respectively. Similar concerns about QTc interval prolongation were also raised in several studies that assessed the safety of DLM-containing regimens10,11. Contrary evidence of no association between these drugs and QTc change also exists12,13. A trial from Motta et al.13 reported differences in QTc prolongation across different BDQ and Pa combinations; however, none of them was considered clinically significant. The findings among the different aforementioned reviews highlight the need for a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to quantify the incidence and the comparative risk of QTc prolongation upon using these drugs, both individually and in combination, to guide the need for clinical monitoring and ensure patient safety.

A limitation of the available studies is that they did not specify the cardiotoxicity or the risk of QTc prolongation that comes with the use of these drug8,14-21. Understanding the impact of these agents specifically on QTc can benefit both physicians and patients in making informed decisions and can allow physicians to adequately predict, assess, and monitor the cardiac risks following their administration. To our knowledge, no prior meta-analysis has systematically compared the incidence and relative risk of QTc prolongation associated with BDQ, DLM, and Pa, whether used alone or in combination. This study was therefore designed to fill this gap and provide clinicians with a more comprehensive, quantitative assessment of cardiotoxicity risks.

METHODS

Study protocol and registration

This meta-analysis complied with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol (PROSPERO: CRD42024553530).

Search strategy and study selection

We systematically searched seven electronic databases: ClinicalTrials.gov, Cochrane CENTRAL, Embase, ProQuest, PubMed/MEDLINE, ScienceDirect, and SinoMed. The search combined population terms (‘tuberculosis’ OR ‘TB’) with intervention terms (‘bedaquiline’ OR ‘delamanid’ OR ‘pretomanid’). Two authors (MJ and IS) conducted the database searches, and four reviewers (AS, RH, IS, MJ) independently screened records, removed duplicates, and assessed eligibility for potential researches published up until December 2024. References of included studies were also screened for additional relevant records. No restrictions on publication date or language were applied.

Eligibility criteria

To be included, a study had to be: 1) a randomized controlled trial (RCT) or non-randomized controlled trial (NRCT); 2) participants diagnosed with TB; 3) an intervention arm that used any of the novel drugs (i.e. BDQ, DLM, or Pa); and 4) reported outcomes relevant to QTc changes. Exclusion criteria included non-clinical trial study designs and studies of non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection.

Data extraction

A predefined Google Sheet was developed by MJ and IS prior to the data extraction process, which was performed by seven authors (MJ, IS, MFA, SA, YS, AS, RH). The data extracted included the following variables: trial registry codes, principal author’s name, year of publication, trial design, blinding status, country of study, sample size, genders, participants’ mean age, resistance profiles (i.e. rifampicin-resistant TB [RR-TB], multidrug-resistant TB [MDR-TB], pre-extensively drug-resistant TB [pre-XDR-TB], and extensively drug-resistant TB [XDR-TB]), and the HIV status. Data on the administered novel anti-TB regimens, doses, and durations were also recorded. Other anti-TB agents included in the regimens were also noted. Data on the QTc, including mean changes and the proportion of patients with prolonged QTc following therapies, were recorded.

Quality assessment

The quality of each included study was assessed independently by nine authors (CJ, IS, MFA, SA, YS, AS, RH, MAC, HI) using the Delphi Risk of Bias Tool for Clinical Trials22. The tool assesses the following methodological domains: 1) randomization, 2) allocation concealment, 3) baseline similarity, 4) specification of eligibility criteria, 5) blinding (i.e. assessors, care providers and patients), 6) estimates and measures of variability presentation, and 7) the inclusion of intention-to-treat analysis22. Each methodologic criterion scored 1 if ‘yes’, and 0 if either ‘no’ or ‘don’t know’, with 9 being the highest possible overall score23. The assessment of NRCTs was done using the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS)24, which assesses three main domains: 1) selection (i.e. sample representativeness, nonrespondents, exposure measurement); 2) comparability (i.e. controlling for confounding factors); and 3) outcome (i.e. outcome assessment method, statistical analysis). A study with a cumulative NOS score of ≥7 is considered good quality.

Outcome definitions

The outcome of interest was QTc prolongation following the addition of bedaquiline, pretomanid, and/or delamanid to the usual standard of care. The QTc was corrected using the Fridericia formula25. The QTc prolongation grading was done in accordance with the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology of Clinical Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE)26. Concerning our study: grade 3 QTc prolongation is a QTc of >501 ms or a change of >60 ms from baseline; grade 4 is defined as a QTc of >501 ms in addition to associated arrhythmias, i.e. torsades de pointes (TdP), polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT), or severe arrhythmias. The outcomes of interest included: 1) the incidence of grade 3 QTc and grade 4 QTc prolongation among patients receiving novel anti-TB agents; 2) the risk ratio (RR) for developing a prolonged QTc among patients receiving anti-TB agents compared to patients in the control arms; and 3) and the mean change of QTc (ms) following the use of novel anti-TB agents, which is defined as the average change in QTc interval compared to their baseline values.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis and plot synthesis were done using OpenMeta[Analyst] software, Brown University. The overall incidence of grade 3 QTc prolongation was calculated and estimated by taking absolute numbers reported by each study, followed by proportion single-arm meta-analysis. The binary outcome, i.e. risk of QTc prolongation compared to the standard of care (SOC), was reported as RR. The continuous outcome, i.e. the mean change of QTc during the follow-up period was reported as mean difference (in ms). A random-effects analysis model was selected for all analyses due to considerable between-study variability. Subgroup analyses were performed for all outcomes based on the novel anti-TB drugs administered. The I2 statistic was used to assess heterogeneity, with a score of >75% regarded as highly heterogeneous. A p<0.05 was considered significant at a two-tailed 95% confidence interval (CI).

RESULTS

Literature search results

A total of 1184 studies were initially identified from seven electronic databases: PubMed/MEDLINE (n=522), Embase (n=200), Cochrane CENTRAL (n=148), ScienceDirect (n=141), Clinicaltrials.gov (n=75), PROQUEST (n=54), and SinoMed (n=44) (Figure 1). Following the initial removal of duplicate records (n=319), titles and abstracts were screened, and 800 additional records were excluded for the following reasons: irrelevant records (n=535), literature reviews (n=122), observational studies (n=56), systematic reviews (n=13), non-human subjects (n=3), and other (n=70). Of the remaining 65 reports that were eligible for full-text review, 34 were excluded due to full-text unavailability, and 13 were excluded for not reporting QTc changes. Among the excluded articles Diacon et al.27 and Goodal el al.28 were originally included in the initial review but not in the current one as they did not report QTc changes. A total of 18 clinical trials were ultimately selected for qualitative and quantitative analysis.

Overview of trials

Characteristics of included trials

The key characteristics of the included trials (n=18) are detailed in Table 1. The trials were published between 2012 and 2023 across multiple countries, including China, Egypt, Japan, Peru, South Africa, and the United States, among others. The pooled sample size was 3790 participants; the studies ranged from 6 patients29 to 552 patients30. The majority of participants in the trials were men (2494), which was approximately double the total number of women (1296). Ten of the 18 trials were phase II29,31-39, three trials were phase II/III30,40,41, two trials were phase III42, only one trial was phase I/II28,43 and two trials did not specify what phase they were44,45. Four studies were double-blinded31,32,38,40,42. Five trials investigated BDQ in comparison to SOC32,38,41,45; three trials examined DLM in comparison to SOC28,31,40,42, and one trial investigated Pa compared to SOC33. Three trials compared a combination therapy of BDQ and Pa against SOC30,35,39. One trial compared BDQ with DLM37. Four trials that assessed BDQ had no control arm (i.e. one arm design)29,34,36,44. The remaining one trial by Garcia-Prats et al.43 assessed the safety and efficacy of DLM in a pediatric population. Follow-up durations varied across the trials.

Table 1

Baseline characteristics of the included trials

| Authors Year | Study design, phase, blinding | Countries | Arms | Sample size (n) | Sex (n) | Age (years) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Each arm | M | F | Median (IQR) or Mean (SD) | ||||

| Gler et al.31 2012 | RCT, II, double-blinded | Philippines, Peru, Latvia, Estonia, China, Japan, Korea, Egypt, and the United States | DLM 100 mg BID | 402 | 141 | 91 | 50 | 36 (19–63) |

| DLM 200 mg BID | 136 | 95 | 41 | 33 (18–63) | ||||

| SOC | 125 | 89 | 36 | 35 (18–63) | ||||

| Diacon et al.32 2014 | RCT, IIb, double–blinded | Brazil, India, Latvia, Peru, Philippines, Russia, South Africa, and Thailand | BDQ | 132 | 66 | 45 | 21 | 32 (18–63) |

| SOC | 66 | 40 | 26 | 34 (18–57) | ||||

| Dawson et al.33 2015 | RCT, IIb, open label | South Africa and Tanzania. | Pa 100 mg | 2027 | 60 | 38 | 22 | 29.5 (11) |

| Pa 200 mg | 62 | 40 | 22 | 30.9 (9) | ||||

| SOC | 59 | 41 | 18 | 30.4 (10) | ||||

| Pa 200 mg (DR-TB) | 26 | 16 | 10 | 32.4 (10) | ||||

| Pym et al.34 2016 | Single arm, II, open label | China, South Korea, Philippines, Thailand, Estonia, Latvia, Russia, Turkey, Ukraine, Peru and South Africa | BDQ | 233 | 233 | 150 | 83 | 32 (18–68) |

| Tsuyuguchi et al.29 2019 | Single arm, II, open label | Japan | BDQ | 6 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 45.5 (25–73) |

| Tweed et al.35 2019 | RCT, IIb, open label | South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda | BloadPaZ | 240 | 59 | 45 | 14 | 35.1 (13.0) |

| B200PaZ | 60 | 48 | 12 | 33.9 (10.5) | ||||

| SOC | 61 | 46 | 15 | 33.3 (8.6) | ||||

| BPaMZ | 60 | 43 | 17 | 34.0 (12.7) | ||||

| Vasilyeva et al.26 2019 | Single arm, II, open label | Russia and Lithuania. | BDQ | 57 | 57 | 24 | 33 | 28 (18–61) |

| von Groote-Bidlingmaier et al.42 2019 | RCT, III, double blind | Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Peru, the Philippines, and South Africa | DLM | 327 | 226 | 162 | 64 | 32 (18–64) |

| SOC | 101 | 76 | 25 | 31 (18–68) | ||||

| Conradie et al.44 2020 | Single arm, II, open label | South Africa | BDQ | 109 | 109 | 57 | 52 | 35 (17–60) |

| Dooley et al.37 2021 | RCT, II, open-label | South Africa, Peru | BDQ | 84 | 28 | 22 | 6 | 34.5 (21–48) |

| DLM | 28 | 21 | 7 | 32 (19–56) | ||||

| BDQ-DLM | 28 | 20 | 8 | 34 (19–49) | ||||

| Fu et al.45 2021 | NRCT open-label | China | SOC | 103 | 68 | 50 | 18 | 36 (29–50.25) |

| BDQ | 35 | 25 | 10 | 32 (25–48) | ||||

| Esmail et al.41 2022 | RCT, II/III, open label | South Africa | BDQ | 93 | 49 | 34 | 15 | 37 (31–43) |

| SOC | 44 | 28 | 16 | 36 (29–46.5) | ||||

| Garcia-Prats et al.43 2022 | RCT, I/II, open label | Philippines and South Africa | 12–17 years (DLM 100 mg) | 37 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 15.5 (13.3–17.5) |

| 6–11 years (DLM 50 mg) | 6 | 2 | 4 | 9.55 (7.3–11.4) | ||||

| 3–5 years (DLM 25 mg) | 12 | 6 | 6 | 4.35 (3.1–5.9) | ||||

| 0–2 years (DLM 5–10 mg) | 12 | 6 | 6 | 1.65 (0.7–2.5) | ||||

| Goodall et al.28 2022 | RCT, III, open label | Ethiopia, Georgia, India, Moldova, Mongolia, South Africa, and Uganda | BDQ oral | 644 | 196 | 124 | 72 | 32.5 (26.3–41.9) |

| SOC | 187 | 115 | 72 | |||||

| BDQ 6 mo | 134 | 81 | 53 | |||||

| SOC 6 mo | 127 | 77 | 50 | |||||

| Mok et al.40 2022 | RCT, II/III, open label | South Korea | DLM | 168 | 79 | 53 | 26 | 49 (39–57) |

| SOC | 89 | 63 | 26 | 46 (34–60) | ||||

| Nyang’wa et al.30 2022 | RCT, II/III, open label | Belarus, South Africa, and Uzbekistan | SOC | 552 | 152 | 96 | 56 | 37 (18–71) |

| BPaL | 123 | 65 | 58 | 35 (15–72) | ||||

| BPaLM | 151 | 85 | 66 | 35 (17–71) | ||||

| BPaLC | 126 | 84 | 42 | 32 (15–67) | ||||

| Yao et al.38 2023 | RCT, II, double-blinded | China | BDQ | 68 | 34 | 18 | 16 | 46 (13) |

| BDQ | 34 | 19 | 15 | 43 (14) | ||||

| Cevik et al.39 2024 | RCT, IIC, open label | Philipines, Tanzania, Brazil, South Africa, Uganda, Malaysia, Georgia, Russia | SOC | 455 | 153 | 118 | 35 | 34 (26–46) |

| BPaMZ (DS-TB) | 150 | 112 | 38 | 35 (25–45) | ||||

| BPaMZ (DR-TB) | 152 | 94 | 58 | 35 (26-47) | ||||

| Total | 3790 | 2494 | 1296 | |||||

[i] B200PaZ: 200 mg BDQ plus pretomanid and pyrazinamide. BDQ: bedaquiline. BID: twice daily. BloadPaZ: BDQ loading dose plus pretomanid and pyrazinamide. BPaL: bedaquiline, pretomanid, and linezolid. BPaLC: bedaquiline, pretomanid, linezolid, and clofazimine. BPaLM: bedaquiline, pretomanid, linezolid and moxifloxacin. BPaMZ: bedaquiline, pretomanid, moxifloxacin and pyrazinamide. DLM: delamanid. DR-TB: drug-resistant tuberculosis. DS-TB: drug-sensitive tuberculosis. NRCT: non-randomized controlled trial. Pa: pretomanid. RCT: randomized controlled trial. SOC: standard of care.

Intervention characteristics

The regimen of BDQ was largely similar across the trials, i.e. 400 mg once daily for 2 weeks, followed by 200 mg three times a week29,30,32,34,36-38,41,44,45 (Table 2). However, Tweed et. al.35 prescribed a different dosing strategy with 200 mg of BDQ once daily for 8 weeks. Cevik et al.39 also used 200 mg of BDQ once daily for up to 8 weeks followed by a decrease to 100 mg daily for up to 18 weeks. Most studies on DLM prescribed 100 mg twice a day for various durations up to 9 months31,37,40,42,43. However, three studies were dose-ranging studies comparing the 100 mg dose to a higher dose of 200 mg31,42,43. Lower doses were used in one study investigating a pediatric population by Garcia-Prats et al.43 where the dose ranged from 10 mg for infants to 2-year-olds to 100 mg for the older subgroup (aged 12–17 years). For Pa dosing, most studies prescribed 200 mg once daily for between 8 weeks and 26 weeks30,33,35,39,44. However, Dawson et al.33 compared the 100 mg of Pa with 200 mg dose once daily.

Table 2

Bedaquiline, delamanid, and/or pretomanid dosing and accompanying regimens in the included studies

| Author, year, registry | Arms | Intervention | Other anti-TB regimens | Tx Dur (week) | Follow-up (week) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bedaquiline (BDQ) | Delamanid (DLM) | Pretomanid (Pa) | ||||||||

| Yes/No | Dosing regimen | Yes/No | Dosing regimen | Yes/No | Dosing regimen | |||||

| Gler et al.31 2012 | DLM 100 mg BID | No | NA | Yes | 100 mg BID (8 w) | No | NA | Ame/ Cm, Flq | 12 | weekly |

| DLM 200 mg BID | No | NA | Yes | 200 mg BID (8 w) | No | NA | Ame / Cm, Flq | 12 | weekly | |

| SOC | No | NA | No | NA | No | NA | Ame / Cm, Flq | 12 | weekly | |

| Diacon et al.32 2014 | BDQ | Yes | 400 mg qd (2 w), then 200 mg tiw (22 w) | No | NA | No | NA | Ame, Flq, Eto / Pto, Z, E, Cs / Trd, PAS, Cm, Amx/Clv, S | 24 | 24, 72, 120 |

| SOC | No | NA | No | NA | No | NA | ||||

| Dawson et al.33 2015 | Pa 100 mg | No | NA | No | NA | Yes | 100 mg (8 w) | 400 mg Mfx + 1500 mg Z | 8 | days 1, 2, 3, then once weekly for 8 weeks, followed by once every 10 days for 20 weeks |

| Pa 200 mg | No | NA | No | NA | Yes | 200 mg (8 w) | 400 mg Mfx + 1500 mg Z | |||

| SOC | No | NA | No | NA | No | 75 mg H, 150 mg R, 400 mg Z, 275 mg E | ||||

| Pa 200 mg (DR-TB) | No | NA | No | NA | Yes | 200 mg (8 w) | 400 mg Mfx, 1500 mg Z | 8 | 8, 20 weeks | |

| Pym et al.34 2016 | BDQ | Yes | 400 mg qd (2 w), then 200 mg tiw (22 w) | No | NA | No | NA | Ofl, Lfx, Z, Ame, Cs, E, Pto | 24 | 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, 84, 96 |

| Tsuyuguchi et al.29 2019 | BDQ | Yes | 400 mg qd (2 w), then 200 mg tiw (22 w) | No | NA | No | NA | Lfx, S / Lzd, Kan / E, Cs, PAS / Z | 24 | 2, 22, 24, 102, 126 |

| Tweed et al.35 2019 | BloadPaZ | Yes | 400 mg qd (2 w), then 200 mg tiw (22 w) | No | NA | Yes | 200 mg qd (8 w) | Z | 8 | weekly, 8 times |

| B200PaZ | Yes | 200 mg qd (8 w) | No | NA | Yes | 200 mg qd (8 w) | Z | 8 | weekly, 8 times | |

| SOC | No | NA | No | NA | No | NA | H, R, Z, E | 8 | weekly, 8 times | |

| BPaMZ | Yes | 200 mg qd (8 w) | No | NA | Yes | 200 mg qd (8 w) | Mfx | 8 | weekly, 8 times | |

| Vasilyeva et al.26 2019 | BDQ | Yes | 400 mg qd (2 w), then 200 mg tiw (22 w) | No | NA | No | NA | Flq, Lfx, Mfx, PAS, Z, Cm, Lzd, Trd, Cs | 24 | 2, 4, 12,24, 28, 48, 72, 96, 120 |

| von Groote-Bidlingmaier et al.42 2019 | DLM | No | NA | Yes | 100 mg BID (2 m), then 200 mg qd (4 m) | No | NA | NA | 26 | 8, 26, 78, 104, 130 |

| SOC | No | NA | No | No | NA | NA | ||||

| Conradie et al.44 2020 | BDQ | Yes | 400 mg qd (2 w), then 200 mg tiw (22 w) | No | NA | Yes | 200 mg qd (26 w) | Lzd | 26 | 1 to 16, 20, 26, |

| Dooley et al.37 2021 | BDQ | Yes | 400 mg qd (2 w), then 200 mg tiw (22 w) | No | NA | No | NA | Cm, Cs, E, Eto, Z, Lfx, H, Trd, Kan, Lzd | 24 | Every 2 weeks till week 30 |

| DLM | No | NA | Yes | 100 mg BID (24 w) | No | NA | ||||

| BDQ-DLM | Yes | 400 mg qd (2 w), then 200 mg tiw (22 w) | Yes | 100 mg BID (24 w) | No | NA | ||||

| Fu et al.45 2021 | SOC | No | NA | No | NA | No | NA | Lzd, Flq, Cs, Cfz, Z, E /Pto | 36-48 | 12, 24, 36 |

| BDQ | Yes | 400 mg qd (2 w), then 200 mg tiw | No | NA | No | NA | Lzd, Flq, Cs, Cfz, Z, E | |||

| Esmail et al.41 2022 | BDQ | Yes | 400 mg qd (2 w), then 200 mg tiw | No | NA | No | NA | Lfx, Lzd, Z + high-dose H / Eto / Trd | 24-36 | 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 28, 32, 36, 48, 72, 96, 120, 144 |

| SOC | No | NA | No | NA | No | NA | Kan, Mfx, Cfz, Z + highdose H / Eto / Trd | 108-124 | ||

| Garcia-Prats et al.43 2022 | 12-17 years (DLM 100 mg) | No | NA | Yes | 100 mg (6 m) | No | NA | Cm, Lfx, Cs, Pto, Z, E, PAS | 24 | 96 |

| 6-11 years (DLM 50 mg) | No | NA | Yes | 50mg (6 m) | No | NA | Cm, Lfx, Cs, Pto, Z, E, PAS, H | 24 | ||

| 3-5 years (DLM 25 mg) | No | NA | Yes | 25 mg (6 m) | No | NA | Cm, Lfx, Cs, Pto, Z, E, PAS, H, Cfz | 24 | ||

| 0-2 years (DLM 5-10 mg) | No | NA | Yes | 10 mg (6 m) | No | NA | Cm, Lfx, Cs, Pto, Z, E, PAS, H, Cfz, Lzd | 24 | ||

| Goodall et al.28 2022 | BDQ oral | Yes | NM | NM | NA | No | NA | Lfx, Cfz, E, Z, H, Pto | 56 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 28, 32, 36, 40, 44, 48, 52, 60, 68, 76 |

| BDQ 6 mo | Yes | NM | NM | NA | No | NA | Cfz, Z, Lfx, then H + Kan | 36 | ||

| SOC | No | NM | NM | NA | No | NA | Mfx, Cfz, E, Z, Kan, H, Pto | 56 | ||

| Mok et al.40 2022 | DLM | No | NA | Yes | 100 mg BID (9 m) | No | NA | Lzd, Lfx, Z | 36 | 1, 2, 4, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 28, 32, 36, 40, 44, 48, 52, 60, 68, 76, 84, 92, 100, 104 |

| SOC | No | NA | No | NA | No | NA | H, R, Z, E | |||

| Nyang’wa et al.30 2022 | SOC | No | NA | No | NA | No | NA | Lzd, Mfx, Cfz | 24 | 1, 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, 24, 72, 108 |

| BPaL | Yes | 400 mg qd (2 w), then 200 mg tiw (22 w) | No | NA | Yes | 200 mg qd (24 w) | ||||

| BPaLM | Yes | 400 mg qd (2 w), then 200 mg tiw (22 w) | No | NA | Yes | 200 mg qd (24 w) | ||||

| BPaLC | Yes | 400 mg qd (2 w), then 200 mg tiw (22 w) | No | NA | Yes | 200 mg qd (24 w) | ||||

| Yao et al.38 2023 | BDQ | Yes | 400 mg qd (2 w), then 200 mg tiw (22 w) | No | NA | No | NA | Lfx, Lzd, Cs, Cfz | 72 | Every week that is a multiple of 12 up to week 72 |

| BDQ | Yes | 400 mg qd (2 w), then 200 mg tiw (22 w) | No | NA | No | NA | Lfx, Lzd, Cs, Pto | |||

| Cevik et al.39 2024 | SOC | No | NA | No | NA | No | NA | H, R, Z, E, | 26 | 4, 6, 8, 12, 17, 26, 52, 104 |

| BPaMZ (DS-TB) | Yes | 200 mg qd (8 w), then 100 mg qd (17 w) | No | NA | No | 200 mg qd (17 w) | Mfx, Z, H, R, E | 17 | ||

| BPaMZ (DR-TB) | Yes | 200 mg qd (8 w), then 100 mg qd (18 w) | No | NA | Yes | 200 mg qd (26 w) | Mfx, Z, H, R, E | 26 | ||

[i] Ame: aminoglycoside. Amx/Clv: amoxicillin/clavulanate. B200PaZ: 200 mg BDQ plus pretomanid and pyrazinamide. BID: twice daily. BloadPaZ: BDQ loading dose plus pretomanid and pyrazinamide. BPaL: bedaquiline, pretomanid, and linezolid. BPaLC: bedaquiline, pretomanid, linezolid, and clofazimine. BPaLM: bedaquiline, pretomanid, linezolid and moxifloxacin. BPaMZ: bedaquiline, pretomanid, moxifloxacin and pyrazinamide. Cfz: clofazimine; Cm: capreomycin. Cs: cycloserine. DR-TB: drug-resistant tuberculosis. DS-TB: drug-sensitive tuberculosis. E: ethambutol. Eto: ethionamide. Flq: fluoroquinolone. H: isoniazid. Kan: kanamycin. Lfx: levofloxacin. Lzd: linezolid. Mfx: moxifloxacin. NA: not applicable. OBR: optimized background regimen. Ofl: ofloxacin. PAS: para-aminosalicylic acid. Pto: prothionamide. qd: quaque die (once a day); R: rifampicin; S: streptomycin; tiw: three times a week. Trd: terizidone; Tx Dur: treatment duration; Z: pyrazinamide.

TB resistance profile and HIV coinfection status

TB resistance profiles are summarized in Supplementary file Table 1. The TB resistance profiles were reported as follows: MDR-TB (n=1507), RR-TB (n=1348), pre-XDR-TB (n=347), and XDR-TB (n=153). Of the pooled sample, 604 TB patients (15%) were also infected with HIV.

Quality of studies

The methodological quality of the trials is summarized in both Supplementary file Table 2 (for RCTs) and Supplementary file Table 3 (for NRCTs). For RCT studies, two studies received the highest score of 8 out of 938,42, while two studies had the lowest quality score of 3 out of 933,35. Regarding NRCTs, four studies34,43-45 scored ≥7, i.e. were good-quality studies, whereas one trial29 scored 5, which is regarded as fair quality.

Outcome analysis

Incidence of grades 3 and 4 QTc prolongation

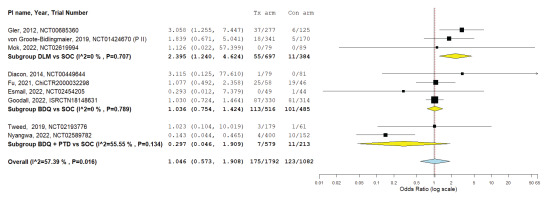

The pooled incidence of grade 3 QTc prolongation varied across regimens (Table 3). Combination therapies, particularly BDQ+DLM, showed the highest rates, while single-drug regimens generally had incidences ≤5% and were comparable to SOC. Grade 4 events were rare, with only four cases reported across three studies, two in BDQ arms and two in SOC arms. Compared with SOC, DLM monotherapy significantly increased the risk of QTc prolongation, whereas BDQ and BDQ+Pa did not (Figure 2).

Table 3

Grade 3 QTc changes

[i] B200PaZ: 200 mg BDQ plus pretomanid and pyrazinamide. BDQ: bedaquiline. BloadPaZ: BDQ loading dose plus pretomanid and pyrazinamide BPaMZ: bedaquiline, pretomanid, moxifloxacin and pyrazinamide. DLM: delamanid. DR: drug-resistant tuberculosis. DS: drug-sensitive tuberculosis. MDR-TB: multidrug resistant TB. Pa: pretomanid. Pre-XDR-TB: pre-extensively drug resistant TB. SOC: standard of care. TB: tuberculosis. Est: estimate.

Only three of the eighteen studies reported an incidence of grade 4 QTc interval prolongation28,29,43; two cases of grade 4 QTc interval prolongation were reported from two BDQ receiving arms28,29 and two other cases were reported from SOC receiving arms28. The Garcia-Prats et al.43 dose-increasing trial did not report any grade 4 QTc interval prolongation in any of DLM-receiving arms.

Relative risk of prolonged QTc interval compared to SOC

Among reporting studies (n=9), DLM-receiving arms were associated with a significant risk of QTc interval prolongation compared to SOC (RR=2.27; 95% CI: 1.21 – 4.24) (Figure 2). No significant difference in the risk of prolonged QTc interval was found with either BDQ alone (RR=1.03; 95% CI: 0.82–1.29) or in combination with Pa (RR=0.31; 95% CI: 0.05–1.85).

Mean change of QTc interval

Details on the mean change of QTc interval were provided by five studies30,32,33,36,37 (Table 4). Diacon et al.32 found a considerable increase in the mean QTc interval in those receiving BDQ compared to SOC (15.4 vs 3.3 ms). Dooley et al.37 also reported a similar value of 12.3 ms (95% CI: 7.8–16.7) among those receiving BDQ. Meanwhile, Vasilyeva et al.36 only reported a 1.4 ms increase in QTc interval. Regarding DLM, Dooley et al.37 reported an increase of 8.6 ms (95% CI: 4.0–13.1) among DLM-only recipients; when combined with BDQ, there was a considerable two-fold rise in the QTc interval (20.7ms; 95% CI: 16.1–25.3). Among those receiving Pa, Dawson et al.33 reported a mean QTc interval increase of 11.1 ms with the 100 mg dose and 17.1 ms with the 200 mg dose, which were higher than the SOC (6.5 ms). Interestingly, Nyang’wa et al.30 was the only study to find a decrease in the QTc interval; compared to the SOC at a 24-week follow-up, the combination regimens of BPaLM, BPaLC, and BPaL decreased -18.1, -5.4, and -20.0 ms, respectively. Pooled analyses were not performed due to lack of sufficient data and differences in interventions.

Table 4

Mean post-treatment change of QTc interval in reporting studies

| Author Year | Drugs of concern | Study arms | Sample size (n) | Mean change of QTc (milliseconds) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 95% CI | ||||

| Diacon, 2014 | BDQ | BDQ | 79 | 15.4 | NA |

| SOC | SOC | 81 | 3.3 | NA | |

| Dawson, 2015 | Pa | Pa 100 mg | 60 | 11.1 | 5.7–16.5 |

| Pa | Pa 200 mg | 62 | 17.1 | 15.1–20.4 | |

| SOC | SOC | 59 | 6.5 | 8.0–14.3 | |

| Pa | Pa 200 mg (DR-TB) | 26 | 11.1 | 5.7–16.5 | |

| Vasilyeva, 2019 | BDQ | BDQ | 57 | 1.4 | NA |

| Dooley, 2021 | BDQ | BDQ | 28 | 12.3 | 7.8–16.7 |

| DLM | DLM | 28 | 8.6 | 4.0–13.1 | |

| BDQ + DLM | BDQ-DLM | 28 | 20.7 | 16.1–25.3 | |

| Nyang’wa, 2022 | SOC | SOC | 152 | 0a | 0 |

| BDQ + Pa | BPaL | 123 | -20b | -25.1–14.9 | |

| BDQ + Pa | BPaLM | 151 | -18.1b | -23.4 – -12.8 | |

| BDQ + Pa | BPaLC | 126 | -5.4b | -10.3 – -0.6 | |

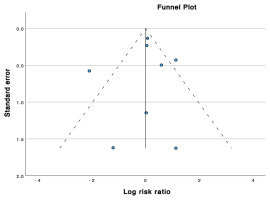

Publication bias assessment

The funnel plot in Figure 3 depicts a visually symmetrical distribution of studies. Egger’s regression test demonstrated a low risk of publication bias (p=0.812).

Heterogeneity analysis between studies

The pooled analyses of overall QTc prolongation incidence showed a relatively high heterogeneity (I2=74.98%) (p=0.001). Each study had different regimens incorporating one or more of the novel drugs BDQ, DLM or Pa, as well as variations in the duration of the treatment, background regimen, and sample size. Further subgroup analyses revealed high heterogeneity among the BDQ+Pa subgroups (I2=89.82%) and moderate heterogeneity among the BDQ (I2=63.86%) and SOC (I2=56.7%) subgroups. The remaining subgroups (i.e. BDQ+DLM, DLM, and Pa subgroups) had very low heterogeneity (I2=0%) due to the low number of studies for each subgroup (between 1 and 2 studies).

DISCUSSION

Since the discovery of the first antibiotic, penicillin by Alexander Fleming, the treatment of infections was revolutionized; however, their effectiveness had a rapid decline due to the wide spread of antibiotic-resistant strains, creating the need for strict usage of antibiotics and continuous search for new treatment alternatives46-48. Due to increased resistance profiles the pharmacotherapeutic strategy for DR-TB treatment continues to evolve. The latest update to the WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis49 has given two new recommendations for DR-TB treatment: 1) a 6-month BPaLM regimen for patients with RR-TB, MDR-TB, and pre-XDR-TB; and 2) a 9-month all-oral regimen in patients with MDR/RR-TB in whom fluoroquinolones resistance (i.e. pre-XDR-TB) has been excluded. Concerning this recommendation, determining the effect that novel anti-TB agents have on the QTc interval is particularly relevant for understanding the cardiac and arrhythmogenic risks to DR-TB patients.

This study aimed to evaluate the impacts that BDQ, DLM, and Pa – individually or in combination – have on the incidence and risk of QTc interval prolongation, as well as the mean change of QTc interval, based on published clinical trials. We found that, when added to the SOC, BDQ, DLM, and Pa when used individually, had incidence rates of 2.6%, 3.1%, and 5.1%, respectively, which are comparable to the SOC (3.4%). When it comes to the relative risk, only DLM-receiving arms showed significant risk of QTc interval prolongation compared to the controls (RR=2.27; 95% CI: 1.21–4.24).

Our pooled analyses estimated that when used alone, the drugs posed an insignificant difference in the risk of prolonged QTc compared to SOC. This correlates with a previous systematic review on BDQ-containing regimens which reported a relatively low incidence of QTc prolongation50. Moreover, the risk of serious dysrhythmias and grade 4 prolongation is generally considered low; in our study, the incidence of grade 4 prolongation among patients receiving BDQ-containing regimens was reported in only 2 cases51-54. However, a scoping review found a higher incidence of prolonged QTc with BDQ+DLM-containing regimens10. Although it was suggested that Pa may not be associated with an increase in QTc, the possibility of its effect on QTc length when combined with other drugs (BDQ, clofazimine, and fluoroquinolones) still mandates periodic QTc monitoring. Our findings suggest that the effects of combining ≥2 agents may produce exponential rather than additive effects on the incidence of QTc prolongation, i.e. BDQ+DLM (25% [9.0–41.0]) and BDQ+Pa (7.3% [1.4–16.8]). This is particularly relevant considering the 2022 World Health Organization updates that want to standardize the implementation of BPaL/BPaLM regimens in the clinical setting.

With regard to the mean QTc change, the trends indicate that BDQ mildly increased the mean QTc; Diacon et al.32 and Dooley et al.37 reported a mean QTc change of 15.4 and 12.3 ms, respectively. Although DLM produced a smaller rise in the mean post-treatment QTc (8.6 ms), the combination of DLM-BDQ may produce a higher QTc (20.7 ms). A systematic review by Simanjuntak et al.50 showed that pooled data from both interventional and observational studies reported a mean QTc change ranging from 11 to 52.5 ms following BDQ treatment. In contrast, a study among healthy volunteers found that neither a single administration of 400 mg nor 1000 mg of Pa was associated with any clinical QTc prolongation55. When co-administered with moxifloxacin (400 mg), Pa’s pharmacokinetics were consistent, and the individually corrected QTc effects were attributed to moxifloxacin alone55. Regarding the BPaL regimen, Li et al.55 predicted a 13.6 ms (90% CI upper limit: 15.0 ms) mean QTcN change, which was different from the reported trial by Nyang’wa et al.30 that did not produce a higher QTc compared to baseline. These inconsistencies with regard to the evidence of mean QTc change following BPaL regimen administration should be further investigated.

BDQ’s association with a higher risk of prolonged QTc may be explained by its primary metabolite, N-desmethyl metabolite (M2). M2 has been linked to a higher risk of toxicity, including prolonged QTc, secondary to cellular phospholipids accumulation56. Serum M2 concentration was constant during BDQ administration, which might explain why prolonged QTc occurred following BDQ discontinuation. Furthermore, the risk of prolonged QTc also appears to be associated with other anti-TB drugs, including clofazimine, fluoroquinolones, and Pa56. Our study found a similar trend, in which the combination of BDQ with either DLM or Pa was linked to a higher incidence of prolonged QTc. The Nix-TB study (NCT02333799) reported that at the estimated mean M2 concentration of 0.25 μg/mL, the mean QTcN increased 4.5 ms9,44, which was further increased by the addition of Pa. The mean steady-state secular-trend QTcN was predicted to be 9.6 ms for the 200 mg dose9. The metabolite of DLM, DM-6705, has a similar mechanism to M2, which results in prolonged QTc due to its inhibition of the rapidly activating delayed rectifier potassium channels (iKR) in the cardiomyocytes37. Both DM-6705 and M2 have long half-lives, resulting in the maximal QTc effect of approximately 5–8 weeks and 24 weeks, respectively34.

Our findings highlight that the risk of clinically significant QTc prolongation is greatest with combination regimens, particularly BDQ+DLM and, to a less extent, BDQ+Pa. Therefore, we recommend that clinicians adopt a structured monitoring strategy: a baseline ECG should always be obtained, with correction of any electrolyte abnormalities and careful review of concomitant QT-prolonging medications. For single-agent regimens (BDQ, DLM, or Pa), monthly ECG monitoring after a baseline and a 2-week follow-up is generally sufficient, as QTc changes with monotherapy are uncommon and typically mild. In contrast, for combination regimens, closer early surveillance is warranted, with weekly ECGs during the first 2–4 weeks followed by checks at weeks 6 and 8, then monthly if stable. This schedule reflects the pharmacokinetic profiles of BDQ and DLM, whose active metabolites (M2 and DM-6705) accumulate slowly and can exert maximal QTc effects several weeks into therapy; hence, early and mid-course monitoring helps detect progressive prolongation before it becomes clinically significant. A QTc ≥500 ms or an increase ≥60 ms from baseline should prompt immediate evaluation, correction of reversible factors, and consideration of drug interruption or substitution. These measures provide a balance between patient safety and treatment feasibility, ensuring that potent novel regimens can be used effectively while minimizing arrhythmogenic risk.

Strengths and limitations

This study, to the best of our knowledge, represents the first meta-analysis to assess the effects of the three anti-TB agents (BDQ, DLM, and Pa, alone or in combination) on the QTc interval. The findings in this study exhaustively addressed the incidence and risk of QTc interval prolongation as well as the mean change of QTc interval in each BDQ-, DLM-, and/or Pa-containing regimen pooled from published clinical trials. This study is important since the three studied agents were integrated into the WHO Group A (BDQ, linezolid, and levofloxacin/moxifloxacin) and Group C (DLM, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and imipenem/meropenem) regimens for treating MDR-TB in 2019, as well as the BPaL/BPaLM regimens for treating DR-TB in 20226,57. This study further supports the WHO recommendation to use electrocardiographic screening during the administration of the anti-TB agents, especially for at-risk populations58.

There were some limitations in our study. These include inadequate subgroup analysis for potentially important and relevant confounders, such as treatment adherence, serum drug level, baseline QTc interval, drug resistance profile, and cardiovascular comorbidities. Furthermore, optimized background regimens (OBR) are another important confounding factor as they may also play a role in influencing the QTc interval. As observed in our study, the combination of BDQ with either DLM or Pa increased the incidence of QTc interval prolongation compared to individual drugs alone; the same trends may be observed with other select OBR in combination with any of those agents. These limitations should be the subject for future studies. Another notable limitation is the variability in the period of drug administration, follow-up duration, adjunctive OBR, as well as the incorporation of NRCTs, which amplify the risk of confounding. Furthermore, none of the included studies reported body temperature in relation to QTc prolongation. Knowing that it is biologically plausible for fever and hypothermia to independently increase arrhythmic risk, this remains an unaddressed factor and warrants investigation in future trials.

CONCLUSIONS

While BDQ, DLM, or Pa when used individually did not increase the incidence of QTc prolongation compared with SOC, combining two or more of these agents substantially amplified the risk. This finding carries clear clinical implications: routine ECG monitoring must be considered essential, for all patients treated with a combination of these novel anti-TB agents. baseline and follow-up ECGs to detect early QTc changes must be considered. Equally important, the use of multiple QTc-prolonging drugs should be avoided whenever possible; such combinations should be reserved only for circumstances where therapeutic benefits clearly outweigh the potential for life-threatening arrhythmias.