INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (ICEP) is a rare pulmonary disorder characterized by eosinophilic infiltration of lung tissue and peripheral blood1. The condition primarily affects middle-aged women, with approximately 50% of patients having a history of atopic diseases, such as adult-onset asthma or allergic rhinitis2. ICEP typically presents with an insidious onset and chronic course, manifesting nonspecific symptoms, including low-grade fever, night sweats, weight loss, and malaise. Respiratory symptoms, such as persistent cough and dyspnea, are common, while extrapulmonary involvement is rare2. Diagnosis relies on clinical and laboratory findings, including eosinophilia in 66–95% of cases and characteristic imaging on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT), which often reveals dense, patchy consolidation and ground-glass opacities in the mid-to-upper lung fields bilaterally1,3. Lung biopsy is rarely required, as peripheral eosinophilia, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) eosinophilia, and responsiveness to corticosteroids are typically sufficient for diagnosis. Pulmonary function tests may show variable patterns, with reduced diffusion capacity (DLCO) being common1. Systemic corticosteroids remain the standard treatment, inducing rapid improvement. However, their long-term use is associated with significant adverse effects, and relapses frequently occur during dose tapering. Emerging biologics, particularly mepolizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin-5, offer a promising alternative1. By selectively reducing eosinophil levels, mepolizumab provides effective disease control with fewer systemic side effects. Clinical studies suggest its efficacy in maintaining remission and preventing relapses in steroid-refractory cases4,5. This report presents a case of recurrent ICEP successfully managed with mepolizumab monotherapy, emphasizing its potential role as an effective treatment option in patients unable to tolerate or sustain corticosteroid therapy.

CASE PRESENTATION

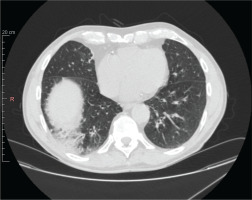

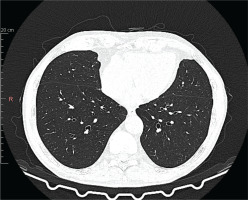

A 65-year-old Caucasian male with a medical history of hypertension, prostatic hypertrophy, and duodenal ulcer disease was admitted to the pulmonology department for the evaluation of a persistent non-productive cough lasting approximately six months, alongside reported weight loss and decreased exercise tolerance. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) demonstrated peripheral ground-glass opacities with thickening of the interlobular septa, bilateral bronchial dilation, and small tumor lesions (Figure 1). Laboratory findings revealed significant eosinophilia in peripheral blood (53.8%) with leukocytosis (13.4 G/L). Diagnostic bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed, during which biopsies of papular lesions on the bronchial walls were taken. Bacteriological cultures, including testing for acid-fast mycobacteria and fungi, were conducted, revealing negative results for Aspergillus fumigatus antigens and antibodies. Histopathological examination indicated mild inflammation with a few eosinophils and no evidence of neoplasia. Cultures from the BAL fluid were also negative. To rule out common causes of eosinophilia, stool tests for parasites were performed, yielding negative results; however, antiparasitic treatment was initiated due to potential false negatives. An extensive autoimmune workup, including various autoantibody tests, returned normal results. Serological tests for atypical bacterial infections were conducted, with borderline results for Bordetella pertussis leading to treatment with clarithromycin; other bacterial infections were excluded. Echocardiography suggested cardiomyopathy, with further cardiac evaluations scheduled based on potential endocardial involvement. Given the pronounced eosinophilia, steroid therapy was initiated, resulting in a significant reduction in eosinophil levels to 1.3%. Three weeks later, BAL revealed that 85% of collected cells were eosinophils. Diagnosis of hypereosinophilic syndrome was established, and treatment with prednisone at 40 mg/day commenced. After one month, a follow-up chest radiograph indicated regression of peripheral nodular shadows and ground-glass opacities, with bilateral pericardial fibrosis. Pulmonary function tests revealed no abnormalities, and inflammatory markers in biochemical tests were negative, with no irregularities in the peripheral blood smear. Follow-up HRCT showed regression of interstitial changes. A decision was made to gradually reduce the prednisone dosage to 10 mg for 14 days, subsequently decreasing to 5 mg for another 14 days before cessation. Three months after stopping prednisone, eosinophilia re-emerged. Repeat bronchoscopy with BAL was performed, and a hematology consultation was scheduled to exclude clonal eosinophilia, which was ruled out, alongside cardiac MRI. Prednisone was reinstated at a maintenance dose of 5 mg/day, as attempts to taper led to recurrent eosinophilia. The patient exhibited a favorable response to treatment, with regression of radiological changes; however, treatment was complicated by recurrent infections. The patient continues to be monitored for any recurrence of infiltrates or eosinophilia upon dose reduction or discontinuation of glucocorticoids. No significant impairment of lung function was noted based on spirometry, body plethysmography, DLCO, and the 6-minute walk test. Secondary causes of eosinophilia were excluded, leading to a diagnosis of idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. Due to the high risk associated with long-term systemic glucocorticoid therapy, a request for mepolizumab treatment was submitted and approved. Subsequent treatment with subcutaneous mepolizumab at 300 mg every four weeks commenced, with the goal of tapering or discontinuing systemic steroids. After two months, systemic steroid treatment was completely halted. Follow-up HRCT six months after starting mepolizumab showed improvement in interstitial and ground-glass opacities in both lungs (Figure 2). Follow-up laboratory work showed eosinophilia level 1.1%, WBC 4.7 G/L and CRP 1.0. He successfully weaned off steroids and has continued on mepolizumab 300 mg monthly dosing with maintained clinical improvement in symptoms. The patient has remained free of disease recurrence to date (over one year). The patient presents to the department every month for drug administration, during which routine laboratory tests are performed, including blood eosinophil level assessment (Figure 3). Additionally, the patient undergoes periodic chest X-ray examinations for monitoring purposes. The medication is well tolerated, and the patient reports no adverse effects. Furthermore, the patient reports an improvement in quality of life, with a decreased frequency of infections and no need for chronic corticosteroid therapy.

Figure 1

Chest high-resolution computed tomography before treatment. Chest high-resolution computed tomography showing peripheral ground-glass opacities with thickening of the interlobular septa

Figure 2

Chest high-resolution computed tomography after treatment with mepolizumab. Chest high-resolution computed tomography showing clear radiological improvement

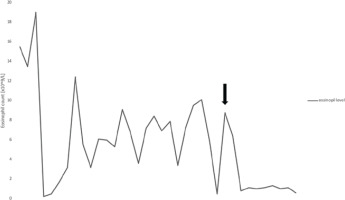

Figure 3

Evolution of the patients’ eosinophil count. The graph illustrates the changes in the peripheral blood eosinophil count during treatment. Attempts to reduce the prednisone dosage resulted in a sharp increase in peripheral blood eosinophils. The black arrow indicates the point at which mepolizumab was introduced into the treatment regimen, eliminating the need for the use of prednisone

DISCUSSION

The gold standard treatment remains corticosteroid therapy due to its rapid and effective response. A dramatic subjective improvement in respiratory symptoms is often observed within 48 hours of initiating corticosteroids, with radiological improvement typically evident within a week6. Unfortunately, long-term corticosteroid use is associated with numerous potential adverse effects, including recurrent infections, metabolic disturbances, osteoporosis, hypertension, weight gain, skin problems, gastrointestinal issues, myopathy, cataracts, glaucoma, mood changes, and depressive disorders7. To minimize these risks, corticosteroid doses are gradually tapered once symptoms are controlled. However, this often leads to disease relapse and the recurrence of symptoms. Relapses are common, with up to 50% of patients requiring long-term low-dose oral corticosteroids or high-dose inhaled corticosteroids to maintain disease control. These relapses are typically managed with high doses of corticosteroids6. Mepolizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting IL-5, presents an excellent alternative to long-term corticosteroid therapy for patients with ICEP. Mepolizumab has been FDA-approved for treating eosinophilic asthma as an add-on therapy for severe cases unresponsive to standard treatments, hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) lasting at least six months, and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA)8. Off-label, it has also been used in some patients with eosinophilic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)9. The off-label use of mepolizumab for CEP has been reported in isolated case reports, with fewer than 100 documented cases in the literature8,10-17. These reports indicate that monthly subcutaneous injections of mepolizumab at doses ranging between 100–300 mg have been associated with improvements in respiratory symptoms, imaging findings, and blood eosinophil levels within four to six months. However, in some of these cases, maintenance corticosteroid doses were continued alongside mepolizumab due to concerns about symptom relapse8. In the case we presented, the use of mepolizumab allowed for the complete discontinuation of prednisone and the achievement of sustained disease remission, which has been maintained for over a year. Additionally, mepolizumab was better tolerated by the patient and did not result in recurrent infections, significantly improving both prognosis and quality of life. It should be noted, however, that randomized controlled trials (RCTs) directly comparing the efficacy of mepolizumab with corticosteroids in ICEP are currently lacking. The available medical literature consists primarily of case reports suggesting the efficacy of mepolizumab in treating ICEP. For instance, Murillo et al.13, in their literature review, gathered 34 case reports and two case series involving monoclonal antibody management. Their findings indicate that the majority of ICEP patients treated with mepolizumab are symptom-free after one year, with some cases reporting remission lasting up to 36 months13. Delcros et al.4, in a recent cohort study, reported no relapses during a median follow-up of 13 months, with blood eosinophil counts returning to normal and pulmonary infiltrates resolving in 71% of patients. Additionally, numerous studies have documented the overall safety profile of long-term mepolizumab use4,5,18.

To date, there is no established optimal duration for mepolizumab therapy. Case reports published thus far indicate that patients typically receive the drug every four weeks, with periodic evaluations for symptom recurrence. Most reported cases describe ongoing treatment without discontinuation (Table 1). The only exception is a case reported by Moritz et al.12, in which a patient received mepolizumab for only three months before treatment was discontinued. Notably, this patient had never received corticosteroids, and Moritz et al.12 reported that the patient remained in remission for over two years without requiring further therapy. In contrast, other case reports have not described treatment discontinuation, making it difficult to determine whether stopping mepolizumab would lead to disease relapse, as is commonly observed with corticosteroid withdrawal. Although our study provides additional support for the use of mepolizumab in the treatment of ICEP, it has certain limitations, primarily related to the duration of therapy. The treatment period is too short to allow long-term prognostication for this patient. Additionally, no attempt has been made to discontinue the drug and observe whether remission occurs. The lack of data on this topic highlights the need for larger-scale studies to investigate optimal dosing, treatment duration, and the risk of relapse following mepolizumab discontinuation. The possibility of masked EGPA cannot be entirely excluded in this patient, despite negative antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) results. EGPA is a rare disease characterized by late-onset asthma, peripheral and tissue eosinophilia, and small-to-medium vessel vasculitis, frequently diagnosed in pneumology departments. The disease shares features with both vasculitis and HES, making diagnosis particularly challenging. Although ANCAs are considered a key diagnostic marker, they are present in only about 40% of EGPA cases. In fact, eosinophilic pneumonia may be the initial presentation of EGPA. Distinguishing EGPA from other ANCA-associated vasculitides and eosinophilic syndromes can be difficult, especially in ANCA-negative cases without classical vasculitis features. Additionally, formes frustes of EGPA – cases in which the disease is partially controlled by corticosteroids prescribed for asthma – may overlap with unclassified systemic eosinophilic disorders, particularly ICEP with minor extrathoracic involvement. Therefore, careful differentiation from mimicking conditions is crucial, particularly in cases where ANCA is negative or vasculitis features are not yet fully established19,20.

Table 1

Selected case reports of mepolizumab for the management of ICEP

| Authors Year | Doses | Number of participants | Duration of follow-up | Age/sex/comorbidities | Outcomes | Relapses | Systemic corticosteroid | Adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyca et al.14 2022 | Every 4 weeks, no dose mentioned | 1 | 9 months | Female, 38 years old, major depression, anxiety, insomnia and weight gain | Improvement after initiation being significant at month 8 | No relapses after initiation | Allows descent and suspension 5 months after initiation | Not described |

| Worth et al.8 2024 | 300 mg monthly | 1 | 8 months | Male, 73 years old, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, sick sinus syndrome with permanent pacemaker placement, thalassemia trait, and seasonal allergies | Clinical improvement, home oxygen no longer required | No relapses after initiation | Low-dose prednisone at 5 mg daily for 5 months, discontinuation after this time | Not described |

| Daboussi et al.10 2023 | 100 mg monthly | 2 | Case 1: 12 months Case 2: 4 months | Case 1: 21 years old patient, high-level athlete, no previous medical history Case 2: Male, 27 years old, active military, asthma one year earlier, an ex-smoker of two-five packs per year | Case 1: asymptomatic, the eosinophil counts dropped to normal range with a complete radiological clearance Case 2: Improvement after mepolizumab | No relapses after initiation | Case 1: Oral corticosteroids were gradually stopped Case 2: Tapering doses of corticosteroids, current dose of 20 mg of prednisone | Not described |

| Moritz et al.12 2024 | 100 mg monthly | 1 | Treatment discontinuation after 3 months | Female, 50 years old, an active smoker, without a notable medical history | Symptom-free state and radiological progress | After over 2 years, the patient showed no clinical or radiological recurrence | None | Not described |

| Kisling et al.17 2020 | 300 mg monthly | 1 | 18 months | Female, 55 years old. Asthma, atopic dermatitis, rhinitis, anxiety, corticosteroid intolerance | Improvement after treatment | No relapses after initiation | Allows corticosteroid decrease | No adverse effects |

| Eldaabossi et al.15 2021 | 100 mg monthly | 2 | Case 1: 15 months Case 2: 6 months | Case 1: Female, 56 years old. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Case 2: Male, 48 years old. Asthma, rhinitis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, depression | Improvement after treatment | No relapses after initiation | Tolerated descent and withdrawal | Not described |

| Sato et al.16 2021 | Case 1: 100 mg every 4 weeks for 14 doses then every 8 weeks Case 2: 100 mg every 4 weeks for 12 doses then every 8 weeks | 2 | Case 1: 36 months Case 2: 24 months | Case 1: Male, 24 years old with asthma, no BAL or biopsy for diagnosis Case 2: Female, 26 years old, asthma and corticodependence | Improvement after treatment | No relapses after initiation | Tolerated decline with suspension at 10 months | No adverse effects |

CONCLUSION

Idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (ICEP) poses a significant challenge for clinicians, both in terms of diagnosis and treatment. The cornerstone of management involves first excluding other, more common causes of eosinophilia, followed by maintaining sustained remission. Attempts to taper corticosteroid therapy often lead to disease relapse and a subsequent rise in peripheral blood eosinophil levels. On the other hand, long-term corticosteroid use is associated with numerous adverse effects. An excellent alternative in such cases is the use of monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-5, which is better tolerated by patients, avoids many of the negative consequences of corticosteroid therapy, and enable long-term remission. However, there remains a lack of randomized controlled trials to evaluate the efficacy, tolerability, and superiority of this treatment compared to corticosteroids, particularly in patients who are corticosteroid-dependent or intolerant.