INTRODUCTION

From mild to severe symptoms and from sporadic cases to a pandemic, seasonal influenza (seasonal flu) affects 5–15% of the worldwide population leading to about 3 to 5 million severe cases requiring hospitalization and about 290000 to 650000 respiratory-related deaths1-3. This viral disease caused by influenza viruses occurs mainly during the cold season in the northern and southern hemispheres while it can be recorded at any time of year in tropical regions2.

Symptoms of flu that begin after an incubation of 1–4 days include typical signs of upper respiratory tract infection (such as cough, a runny nose, and sore throat), and other manifestations like sudden fever, chills, muscle and joint pain, fatigue, and headache that usually last around a week2-4. These signs could, however, be life-threatening among high-risk individuals (children, pregnant women, the elderly, persons with chronic diseases, etc.) where pneumonia, sepsis and secondary bacterial infections could be observed in severe cases2,3. Viral shedding begins about 24–48 hours prior to the onset of the symptoms and the transmission occurs mainly after sneezing and coughing through direct or indirect contact with infectious droplets in crowded places which contribute significantly to the spreading of the virus2.

The influenza vaccine, which has been used since 1945 is seen as the safest and the most cost-effective tool to prevent influenza infections and complications1,5,6. This vaccine is recommended annually by the World Health Organization (WHO) for high-risk categories including pregnant women, children aged 6 months to 5 years, persons aged >65 years, people with underlying medical disorders, and healthcare professionals3. Healthcare workers (HCWs) can also be included in these categories. In fact, in addition to the increased risk of getting influenza at work from both patients and infected colleagues7, HCWs are also at risk of exposure from the broader community (public transportation, home interactions, etc.)8. For these reasons, HCWs are 3.4 times more at risk of developing seasonal flu than the adult population9 and some estimates show that one in four HCWs could contract the disease in a mild influenza season10. Consequently, they constitute a source of infection for patients, coworkers, and family members11,12. Thus, by getting vaccinated, HCWs will protect not only themselves from the infection but also their colleagues, relatives and patients9. It has been shown that immunizing HCWs lowers influenza disease by 29%, healthcare visits by 52%, and fatalities from all causes among aged individuals by 55%1. In addition, vaccination will indirectly reduce the rate of absenteeism and consequently limit the ensuing disruption of medical services1,13. However, despite the above-mentioned benefits of the vaccines and the recommendations of the WHO and the national health authorities, vaccine coverage remains low among HCWs in most countries, especially in low-and-middle income ones1,5,6,14-23.

Algeria, where about 2 to 7 million persons are affected annually resulting in about 2000 deaths, and where 10% of medical consultations are related to flu-like syndromes (caused mainly by subtypes A(H1N1) and A(H3N2), and B/Victoria lineage influenza viruses), the vaccine [intended to provide protection against four distinct flu viruses, including two influenza A (H1N1 and H3N2) and two influenza B viruses (Victoria and Yamagata)], is provided free of charge to high-risk categories including HCWs24. However, no data are available regarding vaccination coverage. Thus, this study was conducted to describe the level of knowledge, attitude, and uptake of seasonal flu vaccine among Algerian HCWs.

METHODS

To assess the knowledge of healthcare workers about seasonal influenza and their uptake and intention towards vaccines, a web-based cross-sectional survey was conducted in Algeria, using a self-administered questionnaire. The survey took place from 28 December 2022 to 29 May 2023, by sharing a Google Forms link on social media platforms targeted at the relevant population that includes mainly Facebook groups and pages dedicated for healthcare workers. All healthcare workers aged ≥18 years, living and working in Algeria were eligible while healthcare students were not allowed to participate in this survey.

The minimum sample size was calculated using the equation:

where Z2=1.96 for α=0.05 (95% CI), p=0.5 (we assume that 50% of the population accepted the flu vaccine), q=1-p, and e is the accepted margin of error chosen to be 10% (e=0.10), giving n=97.

Participation in the study was voluntary, and no financial incentives or compensations were provided. Before any data were collected, each participant gave informed consent online. According to the Declaration of Helsinki Ethical Principles, participants could discontinue the survey at any moment, and those who refused consent were not permitted to continue with the study. Participants’ identities were kept anonymous, while the Scientific Committee of the Faculty of Natural and Life Sciences, University of Djelfa signed the approved protocol.

The self-administered questionnaire (see Supplementary file for English version) was prepared in both Arabic and French after reviewing previous literature related to seasonal influenza attitudes and knowledge in different countries7,9-11,15,17,25. It included 23 multiple-choice items divided into three sections: sociodemographic, professional, and health characteristics (e.g. sex, age, experience, chronic diseases), knowledge level about seasonal influenza (with 10 yes/no knowledge items), and its vaccine (7 yes/no/ I don’t know items), and attitudes towards seasonal influenza vaccines.

Statistical analysis

Data were extracted from the Excel sheet and analyzed using SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA, 2011). They were first presented as frequencies (n) and percentages (%). Chi-squared (χ2) and Fisher tests were used to assess the association between dependent and independent variables to assess the relation between seasonal influenza vaccine acceptance and the sociodemographic characteristics. Factors with a p≤0.10 in the univariate analysis were included in the logistic regression model to confirm their association with seasonal influenza vaccine acceptance. All statistical analyses were performed with a 95% confidence level (CI) and a level of significance of p<0.05.

RESULTS

Sociodemographics

A total of 122 healthcare workers completed the questionnaire, after excluding those who did not meet the inclusion criteria, 112 individuals made up the final sample with a distribution of 56.3% and 43.7% of medical and paramedical staff, respectively. The sample was predominately female (62.5%) with a slightly higher percentage of married individuals (51.8%). Most participants were aged 18–30 years, followed by those in the 31–40 years age group. More than half of the participants had <5 years of experience (53.6%), the majority worked in the public sector (88.4%), and were evenly distributed across different work locations, with the Department being the most common place of work (42.9%).

In terms of health status, nearly a quarter of participants (23.2%) had chronic diseases with hypertension and diabetes being the most common diseases. In addition, a significant portion of participants (43.8%) reported having allergies, while 9.8% were smokers.

Regarding COVID-19 status, the majority of participants (84.8%) reported being infected, while slightly over half of the participants reported having received the COVID-19 vaccine (52.7%) (Table 1).

Table 1

Sociodemographic and health characteristics of the study population

Knowledge about seasonal influenza and seasonal influenza vaccine

Overall, participants demonstrated a high level of correct knowledge about influenza, with an average of 85.89% correct responses across all items. Specifically, knowledge levels were >89% in 6 out of 10 items, and >77% in 9 out of 10 items. The lowest correct response rate was 59.82% for the item: ‘Influenza causes mild symptoms only; therefore, it cannot be considered a serious disease’.

Regarding the vaccine, participants showed a good understanding of the nature and benefits of the influenza vaccine, with an average of 72.7% agreeing with the statements. Correct response rates varied from 64.3% for the item ‘The influenza vaccine is effective at preventing influenza’ to 85.7% for the item ‘The influenza vaccine reduces the risk of hospitalization and death’ (Table 2).

Table 2

Knowledge of the study population about seasonal influenza (SI) and its vaccine

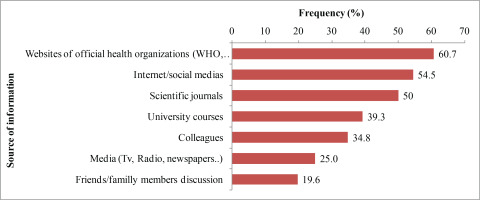

The most trusted sources (60.7%) of vaccine information were official health organization websites (WHO, MOH), followed by the internet and social media (54.5%), and scientific journals (50%). Traditional media (25%) and personal discussions (19.6%) were less relied upon (Figure 1).

Attitude toward seasonal influenza vaccine

Results revealed that 26.8% of the participants had the seasonal influenza vaccine before the COVID-19 pandemic, 17% had it during the pandemic, and 24.1% in 2022–2023. Nearly half of participants (48.2%) stated that COVID-19 had not changed their attitude toward the influenza vaccine, while 39.3% and 12.5% said their attitude had changed in favor or against the vaccine, respectively.

Regarding their attitude, 58.9% of participants were in favor of vaccination, 33% were hesitant and 9% were against the vaccine (Table 3). The main reasons for acceptance were: to protect family (98.5%) or patients (95.5%), and because the disease could be severe (95.5%), while the reason for rejection were related to fear of side effects (100%), and effectiveness of the vaccine (88.9%), and other beliefs related to the severity of the disease (88.9%) and the profit motive of pharmaceutical laboratories (88.9%) (Figure 2).

Table 3

Attitude of the study population toward seasonal influenza vaccine

When asked about their recommendations regarding the seasonal influenza vaccine, respondents mostly mentioned the need for intensified awareness campaigns (37.5%) and providing information about the vaccine content (29.5%). Additionally, 22.3% believed that vaccination of people at risk against influenza should be mandatory while only 5.4% agreed that vaccination of HCWs against influenza should be compulsory in Algeria.

Regarding factors associated with vaccine acceptance, logistic regression results showed that medical staff were more favorable than paramedics (OR=2.34; 95% CI: 1.02–5.35). Furthermore, respondents who worked in Daïras (sub-prefectures) showed more willingness than those working in the Commune (municipality) (OR=3.12; 95% CI: 1.04–9.42). Lastly, having had the COVID-19 vaccine increases the odds of seasonal influenza vaccine acceptance (OR=2.90; 95% CI: 1.29–6.54) (Table 4).

Table 4

Factors associated with seasonal influenza vaccine acceptance of the study population

DISCUSSION

Although not well documented, influenza constitutes a real public health threat in Algeria26, which has pushed the national health authorities to install a sentinel surveillance network Groupe Régional d’Observation de la Grippe (GROG) since 2006 in order to monitor influenza-like illnesses and identify circulating viruses to adapt health measures26,27.

One of the measures adopted by this network is the establishment of annual vaccination before and during the flu season (mainly between October and March)26,27. The vaccine which is provided freely is recommended for high-risk persons including HCWs, with a target vaccination coverage of 35%26,28. However, despite social mobilization through traditional and social media28, some barriers such as the lack of communication outside the flu season, and the fear of side effects, have limited the uptake of the vaccine among HCWs27,29. The rate of vaccination coverage, the willingness and the barriers of rejection have not been studied to our knowledge. Thus, this study has been conducted to evaluate these issues.

Overall, HCWs in our study who were mainly connected to MOH and WHO recommendations (60%), were well-documented regarding seasonal flu and its vaccination with levels of correct responses of 85.9% and 72.9%, respectively. These rates are higher than those reported among Jordanian HCWs11. However, despite these rates of knowledge, the levels of vaccine uptake were low. In fact, 26.8%, 17%, and 24.1% were vaccinated before, during the COVID-19 pandemic and during the 2022–2023 season, respectively. These rates are far lower than the reported rate of uptake in Jordan (62.8%) during the 2021–2022 season11. The small decline observed during the COVID-19 period is not surprising due to its drastic consequence on one’s behavior and the introduction of COVID-19 vaccination resulted generally in the avoidance of the flu vaccine10,30. Other findings show an increase in vaccine uptake during this period15,17,31-34, where the fear of contracting the two diseases (flu and COVID-19) was the main reason for vaccination17. The encouraging finding of our study is, however, the increase of vaccine uptake during the 2022–2023 season, an expected result as COVID-19 served as a motivator for adopting good public health behaviors10. In this way, 39.3% of the participants reported that COVID-19 has positively changed their attitude toward the influenza vaccine. Similar observations were also reported among the general population35 and healthcare workers in Italy36 and in Ireland37. In addition, 70.97% of HCWs and 81.82% of resident doctors in Italy perceived that flu vaccination would be more important during the first vaccination season after the emergence of COVID-1931.

Another interesting finding is that 58.9% of the participants were in favor of vaccination despite their uptake status. However, this rate remains lower than the rates of willingness reported in Southern Italy (68%)25, in China (74.89%)14, and in Saudi Arabia (79%)30, but slightly higher than the rate reported in Poland (54%)38.

In agreement with previous studies, vaccination motivators of the participants include protection of themselves, their families, and their patients6,17,23, while the most cited barriers include the fear of side effects and the effectiveness of the vaccine6,9,13,19,22,23,37. Another barrier that was particularly cited in low- and middle-income countries include the cost of the vaccine and its availability6,11,19,21. Furthermore, free access to vaccination was the strongest motivator of vaccine acceptance among HCWs in Poland38. These findings suggest the need to ensure the availability of the vaccine and recommendation to be supplied free to high-risk categories including HCWs.

Regarding flu vaccine acceptance predictors, there were two interesting observations: the increased odds of acceptance among medical staff when compared to paramedics and the effect of COVID-19 vaccine uptake on seasonal influenza vaccine acceptance. The same observation was reported in different countries where physicians were more likely to accept the vaccine than nurses7,10-12,17,25,31,38,39. The opposite results were seen in Saudi Arabia where nurses were more likely to be vaccinated during the 2020–2021 season (AOR=2.70), and to declare their intention to be vaccinated in the subsequent year (AOR=2.94)30. The authors related these results, however, to the low number of physicians in the studied sample. Lastly, the positive effect of vaccine acceptance on seasonal flu vaccine intention has been previously documented by Di Giuseppe et al. in Italy25.

Limitations

The results of this study are to be considered in light of some limitations related mainly to the sample size and the sampling approach. The low number of respondents in this study may impact the generalizability of the results, while the online sampling strategy and convenience sample may introduce some selection biases by skipping some groups including older individuals and those lacking an internet connection. Another limitation is related to the self-assessment of vaccine uptake and intention, which may result in social desirability bias.

CONCLUSIONS

The current study provides data on influenza vaccination intention, uptake, and predictors in Algeria. The results indicated a low level of vaccine uptake while vaccine acceptance was reported by about two-thirds of participants. Motivators included protecting families and patients while the most significant barriers were related to vaccine safety. Within our sample, factors associated with vaccine acceptance mainly included the medical profession and COVID-19 vaccine uptake.