Supernumerary or accessory fissures represent the most commonly observed anatomical variation of the lungs both on cadaveric exemplaries and on radiological findings1. Lined by two layers of visceral pleura, an accessory fissure constitutes a cleft that delineates an accessory lobe. It may be missed or misinterpreted in conventional computed tomography (CT), due to inadequate slice thickness, position to the scan plane, or in cases of incomplete fissures. In anatomical studies, accessory fissures are noted at a percentage of 7.5– 35%, whereas in radiologic studies the incidence ranges 8–59%2. Lack of obliteration, which normally occurs in the spaces between bronchopulmonary buds during fetus development, is considered to result in the formation of accessory fissures3.

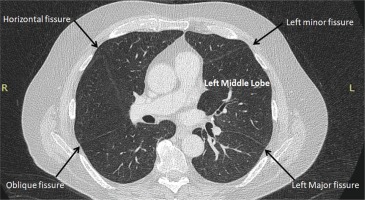

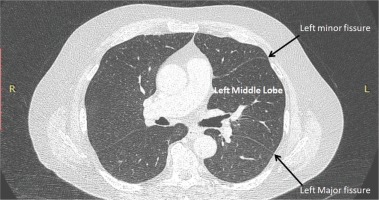

The left minor fissure (Figure 1), an analogue of the right minor fissure, is the second most common accessory fissure and subdivides the upper lobe of the lung into the anterior segment and the lingula, in almost equal sizes (S3/S4). Thus, the lower part is termed ‘left middle lobe’4. An important anatomic landmark for the distinction of the left minor fissure from other upper lobe fissures is the vessel parallel and inferior to the anterior segmental bronchus of the upper lobe (V3b radiological sign). Accessory fissures of the left upper lobe have been classified into four types on CT imaging4. Type I extends from the anterior chest wall with a lateral convexity almost parallel to the lateral chest wall and merges with the major fissure posteriorly at a right angle, separating either the apicoposterior from the anterior segment of the upper lobe (S1+2/ S3), the anterior segment of the upper lobe from the superior segment of the lingula (S3/S4), or the superior from the inferior segment of the lingula (S4/S5). Type II has a sagittal course with medial convexity and separates the superior from the inferior segment of the lingula (S4/S5). Type III shows anteromedial convexity with an oblique orientation from the anterior chest wall and separates the anterior segment of the upper lobe from the superior segment of the lingula (S3/S4). The patient, presented hereby, has a type IV accessory fissure (Figure 2), which emerges as a transverse and almost straight line parallel to the major fissure (S3/S4).

Figure 1

An accessory left fissure subdivides completely the upper left lobe into anterior segment and lingula

Figure 2

An accessory left fissure emerges as a transverse and almost straight line parallel to the major fissure. The lung parenchyma between the two fissures is named ‘left middle lobe’

Among the frequently encountered supernumerary lung fissures2, the inferior accessory fissure, which is the most common (7–20%), has a lateral course on the diaphragmatic surface of the lung from the pulmonary ligament and merges with the major fissure with a forward arc demarcating the medial basal segment (S7) of the lower lobe, which is thus termed inferior accessory, cardiac, retrocardiac, or infracardiac lobe, as a counterpart to the cardiac lobe that is present in most mammals5. Another supernumerary fissure, the superior accessory fissure (1–5%), is encountered at the same level or slightly lower than the minor fissure and separates the basal segments of the lower lobe from the superior segment (S6), which is termed posterior or dorsal lobe5. Other accessory fissures are noted in <3%, including the azygous fissure of the right lung (0.5–1%), which extends from the posterolateral aspect of an upper thoracic vertebral body to the superior vena cava or right brachiocephalic vein and outlines the azygous lobe6.

Awareness of accessory fissures is essential in preoperative as well as bronchoscopy planning procedures, contributes to the localization of pulmonary lesions and facilitates differentiating them from abnormal structures, such as linear atelectasis, pleural scars, wall of bullae, or the pleural lining of pneumothorax2.